Recently I’ve been teaching a seminar on “The Psychology of Happiness” that draws entirely on nonbehavioral literature. It’s one of the most behavioral things I’ve ever done.

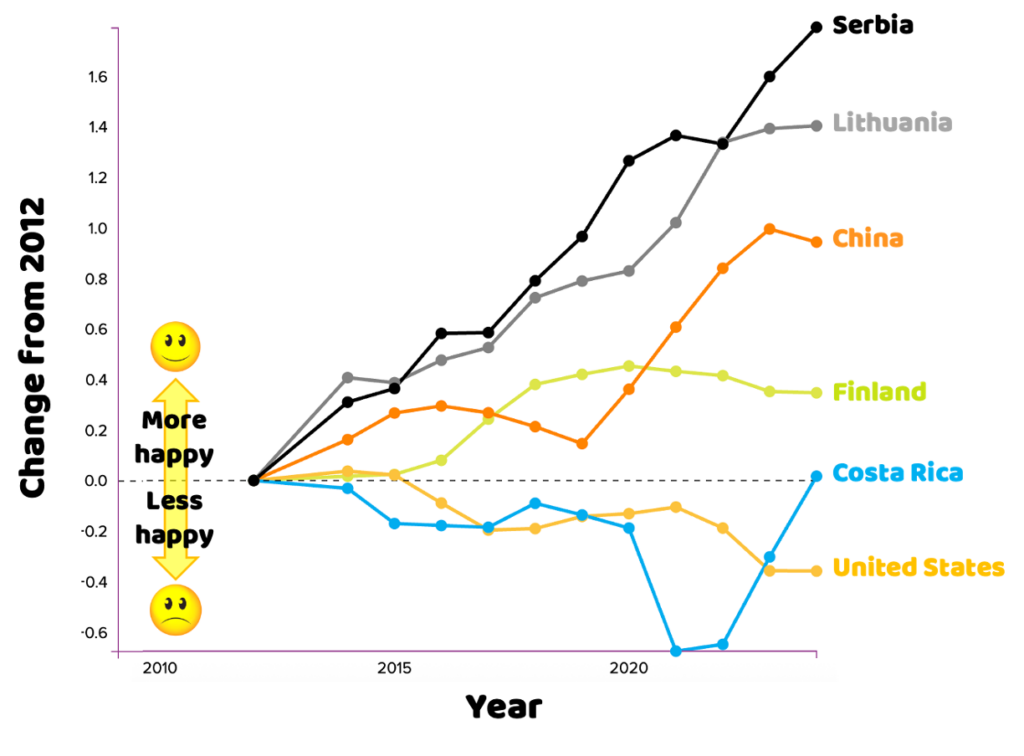

The reason I started offering “The Psychology of Happiness” was simple: Across semesters, I noticed my undergraduate students, especially the seniors, growing increasingly miserable. Students are hardly alone in struggling, by the way. For instance, according to the 2025 World Happiness Report, the United States as a whole, despite its world-leading material advantages, ranks behind 23 other nations in terms of overall population happiness (Postscript 1), and is becoming systematically less happy (for some reasons why, see this post in the excellent Selectionist blog).

Happiness, of course, can be a stretch for anyone who is staring down the barrel of a potentially bumpy life transition. The word best describing my graduating seniors might be demoralized. They are not currently happy, and they are not optimistic that they can ever be. A big reason: During their entire, heavily-scripted school lives they’ve stayed afloat by telling themselves that “I will be okay just as soon as I….” [here, fill in any number of life markers, like get accepted to college or pass this upcoming test or finish College Algebra or whatever]. None of those previous milestones made everything peachy so as they approach graduation many are realizing that not even a diploma will magically confer peace and joy (particularly in light of a very challenging economy, but to be clear, there’s more than external circumstances at work here).

With this as backdrop, the “Psychology of Happiness” course is intended to provide students with an opportunity for a sort of a psychological reset before they plunge into the exciting-but-unforgiving post-baccalaureate world.

The gist of the course is that most people go about their happying (to coin a gerund) entirely wrong. That is, the actions they imagine to be happiness-generating aren’t. Fixes for this are surprisingly simple (in principle at least; reliable implementation takes practice), and as best I can tell, based on anecdotal evidence, students benefit from the course. Most of the time they actually show up to class and, while there, they are actively engaged and display a lot of positive affect (two things that are far from guaranteed with graduating seniors). The students report actually using the techniques we talk about, and more than in any other course I get end-of-term notes from grateful students describing how the course helped them.

What Works, Works

All that aside, however, what you’re probably wondering is how a committed behavior analyst can be comfortable teaching a course that’s “not behavior analytic” (in the sense that nothing my students digest comes from behavior analysis sources).

My answer draws on a favorite saying of ABA pioneer Jim Sherman: “If it works, it’s behavior analytic” (paraphrased from Reed & DiGennaro Reed, 2025). This is not to assert that the only things that work are those that have been conceptualized behavior analytically. Rather, what works — no matter how it’s explained — must tap into the same universal Laws of Behavior on which effective behavioral interventions are based.

Almost none of the massive scientific literature on happiness originates in behavior analysis (Postscript 2), but the literature generally reflects three things that behavior analysts appreciate: it is strongly evidence based (Postscript 3), it focuses on behavior, and it leads to interventions that are relatively easy to understand and implement.

So, though you might imagine that research on something as nebulous as happiness would be chock full of touchy-feely nonsense, what it actually shows, over and over, is that behavior matters. Indeed, what Yale University’s Lauri Santos, creator of that school’s most popular course (“The Psychology of Well-Being;” see Postscript 4), says in introducing her topic is what the title of this post asserts: Happiness is something you DO.

Here’s a selective list of some things you can do to cultivate happiness:

- Seek experiences rather than things or events. People tend to think that accomplishments (like those student milestones mentioned above), or material things (e.g., new car, house, clothes), will make them happy, but at best these yield fleeting positive emotions. This is in part due to “hedonic adaptation” (habituation), and in part because of the human tendency for social referencing, meaning that people tend to chase accomplishments and things that others have defined as desirable. Also, positive experiences tend to produce more lasting happiness than things — for example, it’s better to you use your feet to explore that long-awaited Van Gogh exhibition than to fill that pair of expensive shoes you’ve had your eye on.

- Make social connections. Positive social interactions bolster happiness. These can be intensely intimate, as with a lover or best friend, or superficial and fleeting, as per a brief exchange with a stranger. The sum of all types of social connections is what matters.

- Engage in mindfulness, savoring, and gratitude. Placing focused attention on happiness-producing variables increases their benefits. In casual terms you might say it’s important to both notice these factors and to examine how and why they benefit us (see Postscript 5).

- Move, eat properly, and sleep. Good body upkeep potentiates other factors that promote happiness. It’s harder to be happy when you eat poorly and get too little exercise and sleep.

Sure, given that this is a mainstream area of inquiry the factors mentioned above sometimes are discussed in ways behavioral folks may find imprecise. There can be a lot of mentalistic mumbo-jumbo swirling around the periphery of the more-behavioral stuff. But, c’mon, behaviorists know a behavior when they see one, and it’s telling that happiness behaviors work with or without those mentalistic accompaniments. That’s why, in discussing the varied philosophical perspectives on happiness, a popular primer says:

Happiness, in these views… is not something you simply choose, like a pair of shoes. Rather it is a skill you must cultivate through years of effort. None of [the major thinkers in this area] holds the crazy view that anyone can just… bootstrap herself into happiness. (Haybron, 2013, Happiness: A Very Short Introduction, p. 60, emphasis in original)

10,000 Hours

I don’t get into this with my students, but the above hints at why behavior analysis is the perfect accompaniment to the existing literature on happiness.

An analogy: Many years ago I invited K. Anders Ericsson to present at a behavior analysis conference about his famous work on expertise (operationalized, rather behaviorally, as “reliably reproduceable superior performance”). Ericsson’s work showed that people in far upper extreme of the capability distribution, in many domains of performance, got there through sustained practice — I particularly like his paper showing why so-called “gifted” individuals are not simply recipients of inherited exceptionality. Anyway, Ericsson normally charged a pretty hefty speaker fee, but he waived most of that to speak to us. When I asked why, he said: “Look, we know what a person needs to do over time to achieve extremely high level skill. What we don’t know is how to get people to do that stuff, and I’m hoping you folks can help me with that.”

That pretty well sums up the status of “happiness behaviors” too. Most have been known about for a long time, but listing them isn’t the same as getting people to engage in them regularly. Fortunately, behavior analysts know a thing or two about how to get people to engage in targeted behaviors. Thus, what counts as “instruction” in my class is mostly just setting up contingencies to get students to try out happiness behaviors that their off-kilter lifestyles may not properly emphasize (see Postscript 6). Long story short, the science of happiness provides the raw material for “interventions” that work, and the science of behavior has much to say on how to implement interventions. It’s a potentially sweet match (though see Postscript 7).

Currently, Behavior Analysts Make Almost Nobody Happy (Proof: See Postscript 8)

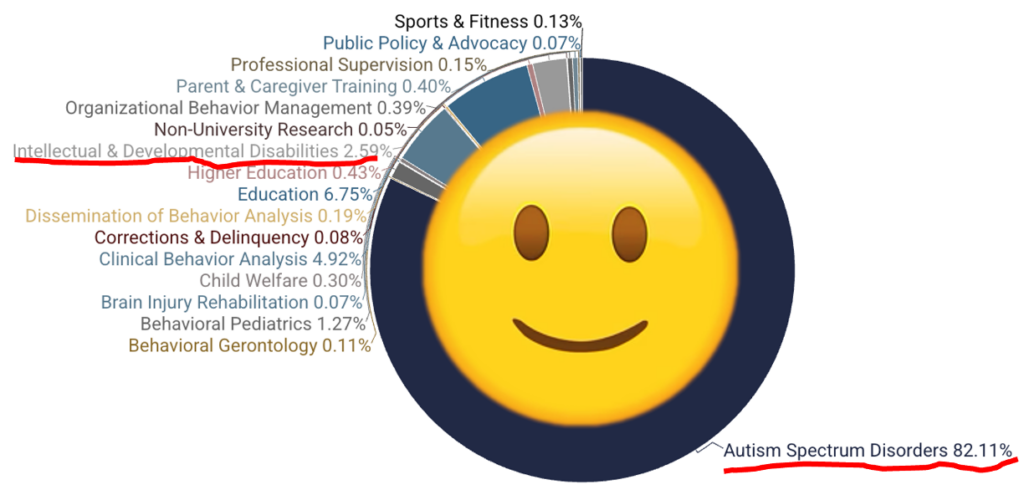

If you’re curious about contributions of applied behavior analysis (ABA) to happiness science, oops, sorry, there’s not a lot to report. Several studies have explored how to promote and measure happiness in persons with intellectual disabilities (Postscript 2), but happiness in typically developing people (those who fall into the “bulge” of the normal distribution) has been all but ignored.

If ever there was a marker for how far ABA has gone down the autism rabbit hole, this may be it. Over the years critics have claimed that a behavioral approach might work in laboratory animal research or interventions for people with disabilities, but it’s irrelevant to the human condition as most people experience it. Ignoring a topic as ubiquitous as happiness is an awesome way to persuade those critics that they are right.

When it comes to addressing happiness head on, Acceptance and Commitment Therapy does much better (see Postscript 9). For abundant reading, try a simple Google Scholar search for “acceptance and commitment therapy happiness.” But warning: If you’re an ABA traditionalist, in examining specifics you’ll confront layers of longstanding philosophical differences between ACT and ABA. Those issues aren’t simple (Postscript 10).

But we needn’t take a position on ACT-ABA disagreements to state, objectively, that if ABA fails to address problems that are widespread and pressing, well, that’s a shortcoming. Healthy applied sciences start with the problems that matter most and get busy sciencing the shit out of them (phrase appropriated with apologies to the film The Martian). The search for meaningful solutions is placed at the fore, and the perfect isn’t allowed to be the enemy of the good.

To be a force in the ongoing human quest for happiness, ABA would need to shift priorities. To be honest, however, I’m not sure if ABA can ever claw its way back out of the autism rabbit hole. We have the tools to accomplish just about anything to improve the human condition, but the financial contingencies of autism treatment are a powerful magnet for our discipline’s expertise — for instance, according to the Behavior Analyst Certification Board, at least 17 of every 20 board certified practitioners focus on autism and other rare conditions. While ABA is busy serving this tiny fraction of the population, millions of people are looking for help with the most general of Big Problems, their happiness (Postscript 11).

It’s true that, due to contemporary developments in the world of autism, more behavior analysts enjoy more demand for their expertise than anyone could have imagined a generation or two ago. But this is selective affirmation. The autism boom has not persuaded anyone that ABA is good for much of anything other than autism. Imagine how the world might reward a discipline that succeeds in making it a happier place.

Resolved: Spread Good Behaviors

Given the timing of this post, how about we close with a good old-fashioned New Year’s Resolution?

Those of us who value behavior analysis spend a lot of time worrying about how to market it to the public. But maybe that’s too narrow a goal. Maybe, more expansively, the job of a behavior analyst should be to promote well-being, however that goal may be achieved.

Sure, in some cases, as Jon Bailey (1991) explained so persuasively, that will mean thinking and talking differently about already-existing behavioral interventions. If that’s all we do, however, we’ll focus on domains of application with already-refined technologies, and given the limited supply of behavior analysts who develop technologies, that’s not many domains.

What if, instead, all of us made it our business to seek out and disseminate everything we can find that promotes productive behavior, regardless of how it’s talked about and where it originates (e.g., mainstream Psychology, exercise science, social work, etc.)?

I know, I know, the standard objection is that this will water down our rigorous science… it’ll make us sloppy thinkers and distract the public from things that we uniquely devised. Maybe that’s a risk, but the potential benefits are: We behavior analysts could become known as folks who care more about helping other people than about advancing our own professional interests, and we might, in sorting out why things we didn’t create work, just manage to grow and expand our science of behavior. Accomplishing even a sliver of that seems like a worthy New Year’s goal.

Postscript 1: More on Happiness in the U.S.

Wealth normally is a pretty fair predictor of national happiness, although the U.S., with the world’s 4th richest economy, is a bit of an outlier in this regard. Among the factors dragging the U.S. down: perceptions of government and business corruption (rank = 37th), healthy life expectancy (56th), and, strangely for a nation that trumpets its egalitarian credentials, perceptions of individual freedom (112th). Regarding that last item, here’s a head-scratcher of a comparison to ponder.

In case you Americans are curious, the happiest U.S. States, in terms of “physical and emotional well being,” are Hawaii, New Jersey, Maryland, Massachusetts, and Florida. The least happy: Tennessee, West Virginia, Oklahoma, Louisiana, Arkansas.

The happiest U.S. cities according to the same metric: Fremont (CA), Irvine (CA), San Jose (CA), Overland Park (KS), Seattle (WA), San Francisco (CA), Columbia (MD), South Burlington (VT), Sioux Falls (SD), and Bismarck (ND). Among the least happy are Gulfport (MS), Brownsville (TX), Toledo (OH), Fort Smith (AR), and Huntington (WV).

Postscript 2: Behavior Analysis Research on Happiness

What little systematic empirical work on happiness has come out of behavior analysis focuses mainly on persons with disabilities (examples below).

- Defining, validating, and increasing indices of happiness among people with profound multiple disabilities

- Increasing indices of happiness among people with profound multiple disabilities: A program replication and component analysis

- Measuring happiness behavior in functional analyses of challenging behavior for children with autism spectrum disorder

- Measuring indices of happiness and their relation to challenging behavior

- Using indices of happiness to examine the influence of environmental enhancements for nursing home residents with Alzheimer’s disease

At the conceptual level, a number of behavior analysts (including Skinner) have suggested that something like happiness results from engaging in behavior that’s reinforced. For instance:

Happiness is a feeling, a by-product of operant reinforcement. The things which make us happy are the things which reinforce us, but it is the things, not the feelings, which must be identified and used in prediction, control, and interpretation. (Skinner, 1976, About Behaviorism, p. 78)

That’s rather general, overly so in fact. One of the lessons of happiness research, translated into behaviorese, is that all reinforcers are not created equal. In any case, a conceptual analysis is an interpretation, a just-so story, and a far cry from an empirically-validated set of best practices.

Postscript 3: Multiple Literatures

When I said the literature on happiness is evidence based, well, that was a selective statement. There is in fact a robust scientific literature, but there’s also a lot of fluff, including hordes of subjectively written self-help manuals and humanities-style reflections on happiness and its causes. I suppose the latter is inevitable, given how much human beings value and worry about their happiness. All of that unscientific stuff about happiness can in fact be taken as evidence for why a science of happiness is needed. If social validity is what people say they care about, and people are buying all of that unscientific stuff, they’re telling us that this topic matters. And on any topic that matters to behavior a science of behavior should offer answers.

It’s also worth noting that a robust literature shows a relationship between happiness and material conditions like wealth, personal safety, etc. The gist of that literature is that material conditions can make you unhappy (e.g., not having enough to eat is a true downer), but they don’t on their own guarantee psychological well being. That requires active “happying,” as discussed here.

Postscript 4: Yale’s Happiness Course

The Yale course has been adapted as a free offering on the Coursera platform, so that anyone can get a taste of what it teaches. There are also versions specifically targeting teens and parents. If you check one of these out, keep in mind that they target everyday people and are pitched at a decidedly non-technical level.

Postscript 5: Mindfulness, Savoring, and Gratitude

These are nothing more than exercises in selective attending, i.e., stimulus control.

Postscript 6: On Practicing Happiness Behaviors

I said my class is mostly practice of happiness behaviors, but it’s a little more complicated than that. My students typically arrive with a behavioral deficit — too few happiness behaviors — but of course most deficits are accompanied by behavioral excesses, and for my students that involves a fair amount of inappropriate rule control. Among the biggest challenges to happiness are rules that take the form of “If I can just have X, I’ll be happy.” For X, substitute a variety of physical acquisitions (e.g., the right clothes, a new car, a house) and life milestones (e.g., passing a certain class, graduating, getting accepted to graduate school, finishing some big project). Most of these rules are socially mediated, which is a gigantic bitch of a hurdle for a generation whose entire existence runs through online social comparison. long story short, a happiness intervention usually requires some defusing of inappropriate rule control.

Postscript 7: The Dark Underbelly of Happiness Science

While it’s true that the independent variables of happiness science are pretty behavioral, I suspect that a lot of behavior analysts will have difficulty with the dependent variables, which consist primarily of psychometric instruments (you can try one of the more popular ones online). Suffice it to say that happiness is a nebulous concept — which even happiness researchers acknowledge. Many like to avoid that term entirely because it suggests joyful emotions that are fairly rare in any life; popular substitutes include thriving and well-being. To me this tilts in the same general direction as Acceptance and Commitment Therapy’s focus on productive functioning both in and out of adversity. With a kind eye you can also see happiness science dancing around what in ACT is called psychological flexibility.

For that reason I suggest not tossing the baby with the bathwater when examining happiness science. The outcomes of interest cut through many discrete behaviors and many environmental contexts… and that is hard to squeeze into the discrete behavioral measurement of traditional applied behavior analysis. Oh, and if you’re hostile to psychometric instruments or self-report measurement, digest this: Behavior analysts who care about happiness in persons with intellectual disabilities also sometimes default to questionnaire measurement, which might be the best anyone can do for the moment when quantifying such a global outcome as happiness. I mean, consider the following equivalence class. Applied behavior analysis has been defined in terms of social significance. Social significance has been defined in part as social validity, which means, in effect, what people say is important to them. Traditionally, people are considered to be happy when they say they are. What’s the big deal? If you can do better, please plunge create your own means of quantifying happiness, but in the meantime it would be a mistake to ignore an impactful area of research and practice simply because we don’t yet have the perfect measurement system.

Postscript 8: The Quantitative Relationship Between Applied Behavior Analysts and Happiness

Does ABA promote happiness? Here’s a prediction: If it does, then the more applied behavior analysts in a country, the happier it should be. Let’s check that out.

The Behavior Analyst Certification Board says that in 2024 there were certified practitioners, at level of training to support the creation of behavioral programming (BACB and BACB-D), in 93 nations. I rank ordered those nations in terms of behavior analysts per capita and divided them into quintiles. Then, for each quintile, using the 2025 World Happiness Report I determined the mean rank among 147 nations in terms of the “positive emotions” component of overall happiness (see Note below). Here are the results.

If that looks like close to a zero correlation, it is: Applying Spearman’s rank-order correlation to individual nations yields rho = .0004 (which as you might guess is not statistically significant).

Sure, this tongue-in-cheek analysis is easy to puncture, for instance by pointing out that even in the U.S., the most behavior-analyst-rich country in the world, the “case load” of residents per behavior analyst is about 4500. Other examples: Australia has one behavior analyst per 73,000 individuals; Korea one for each 157,000; and Honduras on for each 1,080,000. Presumably a lot more behavior-analyst-person-power than currently exists would be required to budge national happiness (well, maybe: if behavioral solutions were scaled up and integrated into national policies, you wouldn’t need to worry about “case load” as defined above).

The question of whether ABA promotes happiness deserves an objective, evidence-based answer that currently we lack. I suppose you could say that social validity data are somewhere in the ballpark of what we’re discussing, but they tend to focus on whether, at a given point in time, consumers are happy with a particular intervention — not whether the intervention left them generally happier.

My main interest in this post is what kinds of interventions applied behavior analysts might devise for insufficient happiness, but even if we set that aside for the moment it’s worth asking what would happen if regular old ABA interventions were evaluated via before-after happiness assessments. That’s a relatively easy innovation that would give us some interesting baseline data. So: would our standard behavioral fixes promote happiness? I’d like to see data that bear on that.

Note: the World Happiness Report meaures positive emotions as “The national average of binary responses [0=no, 1=yes] about three emotions experienced on the previous day: laughter, enjoyment, and interest.” Here are the results. I focused on this measure because overall happiness index includes national wealth, can skew perceptions of happiness. By the way the U.S. ranks 30th internationally on the positive emotions measure

Postscript 9: Acceptance

My course does delve into a few insights from ACT, particularly the notion that unpleasant emotions are natural, unavoidable, and not to be ignored. But my undergrads find ACT very hard to understand — maybe because they are steeped in conventional approaches that seek to eliminate, rather than co-exist with, unpleasant emotions? Anyway, this is a topic for another time.

Postscript 10: Some Commentaries About ABA & ACT

Postscript 11: Inexhaustible Demand for Happiness

Here’s a measure of how obsessed the general public is with the chase for happiness. It’s estimated that each year publishers release over 15,000 new self-help books, many of which overlap wit the topic of this post. According to Google (AI Mode), one publisher alone, Simon and Schuster, lists over 1,000 titles on happiness specifically. This massive publishing market tells us two things. First, lots and lots of people are willing to part with their hard-earned cash for a shot at being happier. Second, what they’re learning from mass-market manuals isn’t very effective — otherwise the there’d be no need for a steady stream of new titles. Presumably behavior analysts could do better, if only they’d dare.

THEME MUSIC

(No, not this or this or this or this — you’re welcome)