Guest Blog by Deirdre M. Muldoon and Emily B. McCarthy

Dr. Muldoon is a senior research scientist at the Center for Autism and Related Disabilities (CARD) of SUNY. She also serves as the SLP for a multidisciplinary team at Albany Medical Center, where she assesses children for communication and feeding difficulties. Dr Muldoon has many years of experience working with families and children with language disorders and challenging behaviors in homes, clinics, and school settings. Her research interest centers on understanding and implementing evidence-based behavioral practices in the areas of feeding management and speech-language pathology. She has published qualitative and quantitative research in the areas of feeding disorders and communication deficits in ASD and developmental disability.

Emily McCarthy is a licensed speech-language pathologist serving individuals across the lifespan in and around Albany, NY. Emily received her master’s in communication sciences and disorders from The College of Saint Rose. Emily primarily works with children and adolescents with speech, language, literacy, and feeding needs. She also has experience serving adults with speech, language, cognitive, and swallowing needs following a stroke and/or TBI. She is passionate about providing evidence-based intervention and parent/caregiver training, and education. Emily’s particular research and clinical interests include pediatric language and feeding/swallowing. She has published research in receptive language interventions for autistic children.

On Receptive and Expressive Language

Language is a shared, social code or system for communication, one that is based on rules and symbols (Owens, 2020). This code can be receptive (e.g, understanding the code when following directions, or understanding a story) or expressive (e.g., expressing thoughts, feelings, or answering questions). Receptive language is analogous to listener repertoires, while expressive language is associated with speaker repertoires. Receptive language refers to comprehension (e.g., finding an object having heard the label, following directions, or understanding a storyline). Expressive language includes repertoires such as requesting/manding, labeling/tacting, questions/intraverbals, or telling jokes and stories.

Expressive and receptive language skills develop differently in autistic children (Kissine et al., 2023). In a meta-analysis, Kwok et al. (2015 found that both language skill sets are equally impaired. Many autistic children experience significant delays in their expressive language repertoire, and many do not go on to use vocal language as their primary means of communication (Mody & Belliveau, 2013; Paul & Roth, 2011). Instead, they may rely on pictures, objects, or other methods of alternative communication (e.g., gestures, paper communication boards, speech generating devices, etc.) (Felton, 2024; Mody & Belliveau, 2013).

Minimally verbal autistic children (i.e., children who expressively use no words or a very small number of words/phrases; Kasari et al., 2013) often also experience receptive language difficulties. Importantly, autistic children with significant receptive language impairments are at risk of persistent communication difficulties, both receptive (understanding communication attempts) and expressive (making communication attempts).

Applied researchers rarely focus on receptive language as an isolated topic, and this is especially the case for children with co-occurring cognitive impairments (Thurm et al., 2021). This gap in research persists despite evidence that receptive impairments, if unaddressed, can contribute to long-term communication challenges (Tarvainen et al., 2020).

For minimally verbal children who have difficulty acquiring an understanding of labels for objects in their environment, teachers and speech-language pathologists face several questions: Should receptive vocabulary and receptive language constructs (e.g., prepositions) be explicitly taught? Will directly teaching receptive vocabulary (listener behavior) help children consistently respond to labels of objects when they are named by a speaker (that is, stimulus generalization; e.g., if a listener hears “ball” can they then receptively identify any ball in the environment; in other words, can the learner generalize the receptive label)? Finally, what evidence-based strategies are most effective for teaching a receptive language or receptive vocabulary? The overarching question is whether directly teaching receptive vocabulary or receptive language (listener repertoires) is an avenue to improving both receptive and expressive language (speaker repertoires) in minimally verbal, autistic children.

First Assess Knowledge of Receptive Vocabulary

To assess receptive vocabulary, there are two primary approaches. One is the use of standardized, norm-referenced assessment tools, which compare the child’s performance to other children. However, these measures often fail to capture the skills of neurodiverse children with receptive language impairments, sometimes yielding only quantitative data on nonfunctional vocabulary (for example, beehive or anchor in the Test of Language Development- 5th ed.; Newcomer & Hamill, 2019; or jungle or stack in the Receptive One Word Picture Vocabulary Test, 4th ed.; Brownell & Martin, 2014). Additionally, such tests may not comprehensively assess a robust, functional vocabulary. For example, a neurotypical child should have a receptive lexicon to 150-300 words by age 2 (Owens, 2020), but the Receptive One Word Picture Vocabulary Test assesses only 44 words for children aged up to 5 years 11 months.

A more functional alternative is to select a bank of frequently occurring and ecologically valid vocabulary (see Gray et al., 2024, for a 100-word bank). Choosing items that are functional, occur frequently, and are easily accessible in the child’s environment makes the assessment process more interesting and potentially more reinforcing. Even so, autistic children with receptive language impairments may not consistently identify such items, highlighting the need for individualized assessment.

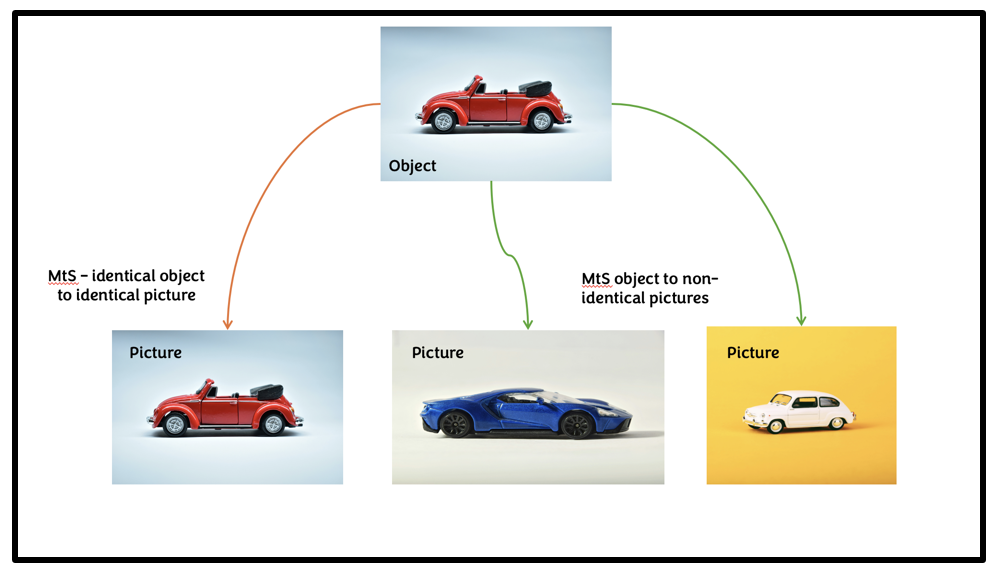

One effective method is a matching-to-sample (MtS) format. MtS is a behavior assessment and teaching method where a sample stimulus is presented (e.g., a ball) and matched to one of a few other comparison stimuli (e.g., a pen, a puzzle, and a ball; Cooper et al., 2007). Correct responses indicate comprehension, while errors identify targets for intervention.

Match-to-sample

MtS is not only useful for assessment, but an effective instructional strategy for relational responding and language acquisition (Barnes-Holmes et al., 2004; Lee et al., 2024; Tovar et al., 2023). Importantly, a correct matching response denotes comprehension (i.e., receptive identification), even without expressive labeling of the object. The correct selection is typically reinforced, which increases the likelihood of accurate responding in the future.

MtS is an evidence-based strategy that can be used for identical matching (e.g., ball to ball), nonidentical matching (e.g., a basketball and a football), cross-stimulus matching (e.g., object and picture), and across modalities (e.g., visual and auditory). For example, if teaching 20 vocabulary words, materials might include 20 objects, 20 identical pictures, and 20 nonidentical pictures (Gray et al., 2024). Instruction can progress from object–identical picture matching, to object–nonidentical picture matching, and finally to nonidentical–nonidentical picture matching. This process builds receptive understanding of labels while also teaching matching skills.

Picture diagram created by Deirdre Muldoon

Prompting

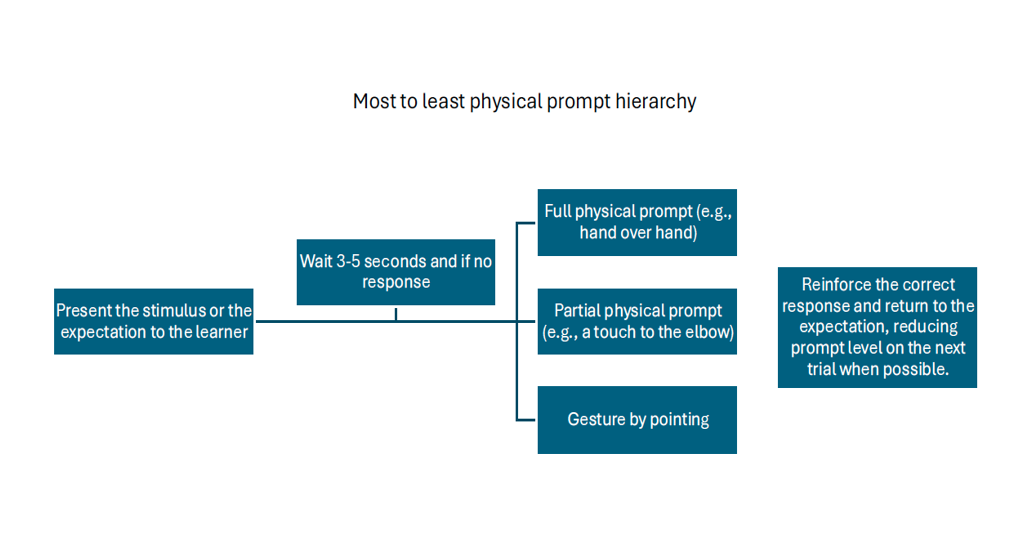

MtS cannot be effectively used with children unfamiliar with the stimuli without systematic prompting (Muldoon & Gray, 2023 ). Prompting is an evidence-based practice (Hume et al., 2021). A hierarchical prompting procedure (e.g., Muldoon & Gray, 2023) can fade support from full physical guidance to gestural prompts, pointing, and ultimately to independent responses. Individualization is essential to maximize benefit and minimize prompt dependence (Weyman et al., 2024). When integrated with reinforcement, prompting, and fading within MtS tasks reduces errors, facilitates discrimination, and supports independent receptive responding (Gray et al., 2024; Muldoon & Gray, 2023).

What about the Receptive-Expressive Connection?

Even children with significant language impairments may attempt expressive production as their receptive vocabulary repertoire grows. For example, teaching “shoe” receptively may evoke approximations such as “sh,” establishing an expressive tact. Beyond tacts, communicative intent may also emerge as the child coordinates spoken approximations with gestures, pointing, or object sharing. Prerequisite skills, such as joint referencing (also called social referencing), joint attention, or reciprocity, are foundational to this process (Owens, 2020).

Conclusion

There is a dearth of information on receptive language intervention with minimally verbal children, particularly those with co-occurring cognitive impairment. Children “on the neglected end of the spectrum” (Tager-Flusberg & Kasari, 2013, p. 468) remain underrepresented in research, despite the pressing need for studies on how to best support them (Thurm et al., 2021). The overarching question is whether purposefully teaching receptive vocabulary or receptive language more broadly (e.g., constructs such as prepositions or temporal concepts) is an avenue to improving both receptive and expressive language in minimally verbal, autistic children. Our initial investigations (Gray et al., 2024; Muldoon & Gray, 2023) suggest that this is an effective and efficient approach, but more research is needed.

References

Barnes-Holmes, D., Barnes-Holmes, Y., Smeets, P., Cullinan, V., & Leader, G. (2004). Relational frame theory and stimulus equivalence: Conceptual and procedural issues. International Journal of Psychology and Psychological Therapy, 4(2), 181–214.

Martin, N., & Brownwell, R. (2018). Receptive one-word picture vocabulary test (4th Edition).

Academic Therapy Publications.

Cooper, J. O., Heron, T. E., & Heward, W. L. (2007). Applied behavior analysis (2nd ed.).

Pearson.

Felton, A. (2024, September 3). AAC: Augmentative and alternative communication for autism. WebMD. https://www.webmd.com/brain/autism/aac-augmentative-and-alternative-communication-for-autism

Gray, R., Muldoon, D. M., & McCarthy, E. B. (2024). Teaching receptive vocabulary to two autistic children: A replicated, clinic-based, single case experimental design. Autism and Developmental Language Impairments, 9, 1-15. DOI: 10.1177/23969415241258699

Hume, K., Steinbrenner, J. R., Odom, S. L., Morin, K. L., Nowell, S. Tomaszewski, B., Szendrey, S., McIntyre, N. S., Yücesoy‑Özkan, S., Savage, M.N., W., (2021) Evidence‑based practices for children, youth, and young adults with autism: Third generation review. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 51, 4013–4032. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-020-04844-2.

Kasari, C., Brady, N., Lord, C., & Tager-Flusberg, H. (2013). Assessing the minimally verbal school-aged child with autism spectrum disorder. Autism research: Official Journal of the International Society for Autism Research, 6(6), 479–493. https://doi.org/10.1002/aur.1334

Kissine, M., Saint-Denis, A., & Mottron, L. (2023). Language acquisition can be truly atypical in autism: Beyond joint attention. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, 153, 105384. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2023.105384

Lee, G. T., Hu, X., & Shen, C. (2024). Brief Report: Increasing intraverbal responses to sub categorical questions via tact and match-to-sample instruction. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 54(12), 4740–4751. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-022-05827-1

Mody, M, & Belliveau, J.W. (2013). Speech and language impairments in autism: Insights from behavior and neuroimaging. North American Journal of Medicine and Science, 5(3), 157-161.

Muldoon, D. M., & Gray, R. (2023). Teaching receptive vocabulary to minimally verbal preschoolers with autism spectrum disorder: A single-case multiple baseline design. American Journal of Speech-language Pathology, 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1044/2023_ajslp-23-00095

Newcomer, P. L., & Hamill, D. D. (2018). Test of Language Development- Primary, (5th edition). Pearson.

Owens, R. E. (2020). Language Development: An Introduction (10th ed.). Pearson. ISBN: 9780135206485

Paul, R., & Roth, F.P. (2011). Characterizing and predicting outcomes of communication delays in infants and toddlers: implications for clinical practice. Language, Speech, & Hearing Services in Schools, 42(3), 331-40. doi: 10.1044/0161-1461(2010/09-0067)

Tager-Flusberg, H., & Kasari, C. (2013). Minimally verbal school-aged children with autism spectrum disorder: The neglected end of the spectrum. Autism Research, 6(6), 468-478. doi: 10.1002/aur.1329

Tarvainen, S., Stolt, S., & Launonen, K. (2020). Oral language comprehension interventions in 1–8-year-old children with language disorders or difficulties: A systematic scoping review. Autism and Developmental Language Impairment, 20, 5. https://doi.org/10.1177/2396941520946999

Thurm A., Halladay, A., Mandell, D., Maye, M., Ethridge, S., & Farmer, C. (2021) Making research possible: Barriers and solutions for those with ASD and ID. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 52, 4646-4650. https://doi: 10.1007/s10803-021-05320-1

Tovar, A. E., Torres-Chavez, A., Mofrad, A. A., & Arntzen, E. (2023). Computational models of stimulus equivalence: An intersection for the study of symbolic behavior. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior, 119(2), 407–425. https://doi.org/10.1002/jeab.829

Weyman, J. R., Imler, M., & Kelly, D. A. (2024). Addressing Prompt Dependency in the Treatment of Challenging Behavior Maintained by Access to Tangible Items. Behavioral sciences (Basel, Switzerland), 14(9), 828. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14090828