Perspectives on Behavior Science soon will publish a thought-provoking collection of essays on the theme of Challenges to Applied Behavior Analysis. Here’s the introduction to the special issue, and see the Postscript for links to the essays. They’re well worth checking out, because no matter what your role in behavior analysis, the reality is that ABA is the discipline’s cash cow. Its successes make everything else more possible and more compelling. As ABA goes, therefore, so goes the entire discipline, and every behavior analyst would be wise to monitor the forces that boost or buffet the well-being of our beloved metaphorical bovine.

This post previews the essay Ronnie Detrich and I contributed to the special collection, called “Seven Dimensions Are Not Enough: Actively Disseminating Applied Behavior Analysis.” Below are some comments about our call to expand ABA’s defining framework.

Applied behavior analysis (ABA) has had many successes worth celebrating, enough to verify that, as Skinner predicted decades ago, it is adaptable to pretty much any problem involving behavior. That’s fortunate, since all of the world’s “Big Problems” are behavior problems. What’s unfortunate, for both behavior analysts and a world badly in need of saving, is that people who are not behavior analysts rarely share in our enthusiasm for the solutions we can create.

Sure, there’s been an incredible boom in demand for autism services (try persuading an overworked practitioner that people aren’t enthusiastic about behavior analysis!). But because that sector of behavior analysis has grown so prodigiously it’s easy to forget that much else in ABA remains in the societal shadows.

I’m not criticizing, just reading the evidentiary tea leaves. For context, here are a some tests you can perform for yourself. Follow the results and I think you will agree: We’re a long way from earning the kind of societal acceptance that will allow ABA to reach its world-changing potential.

- TEST #1: Heward et al. (2022) identified 350 domains of application in which ABA has lent insight and/or created solutions. Pick a random sample of those domains and do a little bibliographic digging to see how much difference those contributions have really made. You’ll find that in a surprising number of the domains there exist just a handful of promising early studies; or maybe just a single research group examining relevant problems. Mst critically, you’ll see few people in the everyday world actually benefitting from those solutions.

- TEST #2: In any application domain of your choice, compare objective measures of the public interest shown in behavior analysis versus in related mainstream disciplines. I’m talking about citation counts, article downloads, and altmetric stats like mentions in social media or news media or public policy documents. In most cases you’ll find that our stuff — even the most popular, in-demand stuff — has caught the eye of a relative few compared to business-as-usual offerings from the mainstream.

- TEST #3 (a thought experiment): Imagine that every single behavior analyst not working in autism suddenly goes on strike. Among the world’s vast population, who would notice?

We Have Met The Enemy And It Is Us

There’s not much about behavior analysis that I would change, but sooner or later we will need to confront the reality that a science that doesn’t sell can’t change the world.

The world’s failure to embrace behavioral solutions is not just discouraging; it’s also an ethical black eye for our discipline. We have proclaimed that people have the right to effective interventions (here and here and here) and have worked very hard to create those interventions. But we’ve seemed less preoccupied with the question of who is responsible for making sure those interventions actually become available to all who might benefit.

The answer to that question is: WE ARE. ABA is our baby, and if we don’t promote it, most likely nobody else will. It follows that if good behavioral solutions are not readily available to people who need them, THAT IS OUR FAULT.

One thing’s absolutely certain: Interventions do not market themselves. Without strategic, intentional dissemination efforts, they are unlikely to become widely adopted. We should already understand this based on our greatest recent success. Although the basics of contemporary autism services have been around for many decades, those services didn’t go fully mainstream in the U.S. until a lot of sweat equity secured health insurance coverage of ABA services. For informative control conditions, look to nations where that isn’t the case. I recently spent a little time in France, for instance, where national health care does not pay for ABA and, as a result, effective autism treatment is available only to the relative few with the financial means to contract for it.

Adoption Is Behavior And Behavior Is Lawful

No matter how effective an intervention is, if basically nobody uses it then functionally that’s the same as if it doesn’t exist, or as if it exists but is ineffective. An example helps to make this point.

A cure for the disease scurvy, once the primary cause of mortality in long-distance sailors, was demonstrated in 1601 on a small fleet of ocean-going vessels. Before the cure was employed, 1 in 5 sailors on that voyage had already died of the disease. Afterward none did. Nevertheless, almost two hundred years passed before this medical innovation was systematically adopted for seafaring fleets. If widely employed right away it would have saved countless sailors (millions died of the disease). Instead, for a couple of centuries it saved essentially no one. My point: Effectiveness is not a hypothetical. It’s the amount of good an intervention does in the world, and that depends heavily on how much it is used in circumstances where good might be accomplished (Postscript 2).

To pivot back to ABA, in our essay Ronnie and I argue that the world is not bettered much if all we do as a discipline is conduct small proof-of-concept experiments, create resource-intensive training clinics, and write persuasive (to us) conceptual analyses. And sadly, outside of autism and a few other domains of application, that describes ABA pretty well.

Why is so much promising behavioral technology languishing on dusty library shelves (Postscript 3) and not being put to good use? Skinner, in “Why we are not acting to save the world” (from 1987’s Upon Further Reflection), identified no shortcoming of behavior analysis; he said, in effect, that the problem is those stubborn everyday people who refuse to see the magnificence of a behavioral approach. On this point Ronnie and I beg to differ.

People who study the adoption of innovations (sadly, mostly not behavior analysts) can tell us a lot that’s relevant here, including:

- Adopting interventions is something people do. As with all behavior, it doesn’t magically occur and is contextually controlled.

- Disseminating means actively manipulating variables that make adoption more likely.

- Innovations are most likely to be adopted when they are compatible with the beliefs, values, and practices of adopters. They must transparently solve problems that people already think are important, and (speaking loosely) make people willing to give up how they already do business.

- The communication that drives successful dissemination requires a functional analysis of adopter verbal behavior.

Seven Dimensions Are Not Enough

Based on the above, no deep reflection is required to perceive that a big reason much of ABA has been ignored is that we behavior analysis haven’t done enough to change adopter behavior. We’ve written papers for behavior analysis journals and presented at behavior analysis conferences, but those are basically non-starters in the dissemination department because they don’t reach the people who decide whether or not to use our stuff on a societal scale.

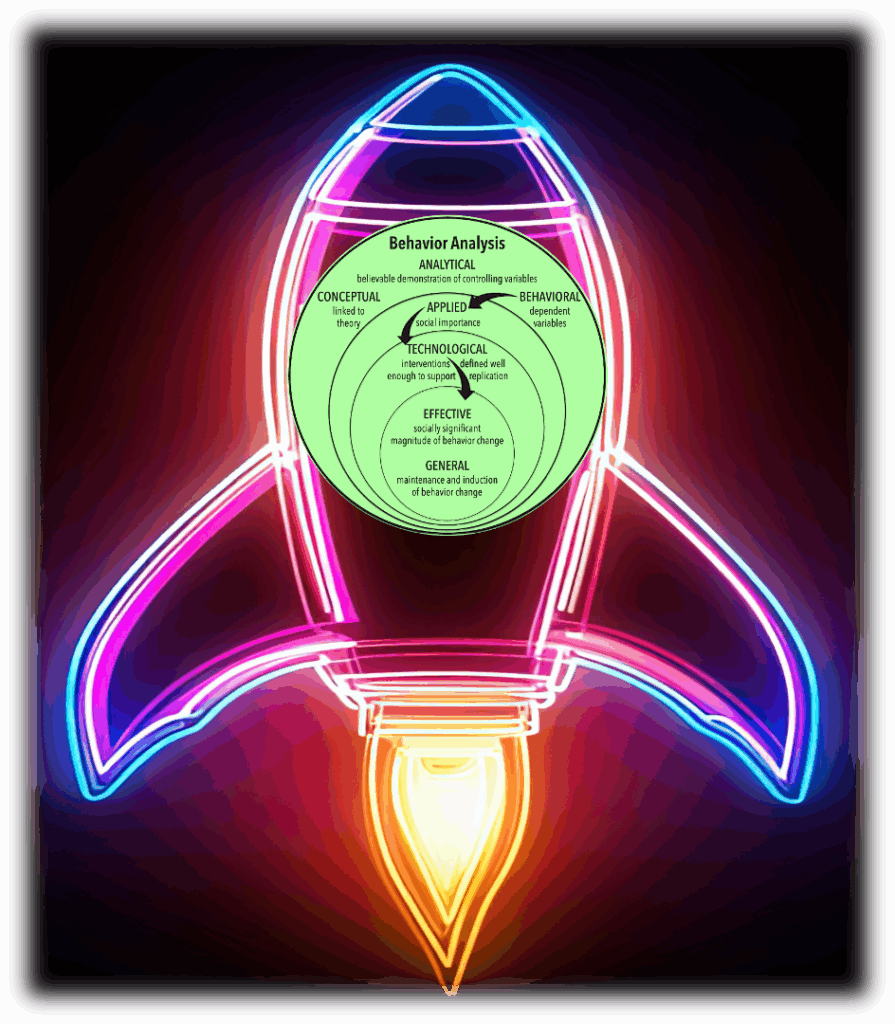

To be sure, Baer, Wolf, and Risley’s (1968) seven-dimension framework is a pretty great prescription for developing innovations of behavioral technology. But it’s nearly silent on how to disseminate the technology. In fact, here is the entirety of what Baer et al. had to say about making the leap from building interventions to getting them adopted:

A society willing to consider a technology of its own behavior apparently is likely to support that application when it deals with socially important behaviors… Better applications, it is hoped, will lead to a better state of society…. it is at least a fair presumption that behavioral applications, when effective, can sometimes lead to social approval and adoption. (p. 91, emphases added)

That is one seriously toothless proclamation… really more of a desperation prayer (“If we do ABA right, maybe, hopefully, possibly someone will want it.”).

But adoption is behavior, and praying doesn’t change behavior.

Nope, adoption is engineering. Think of an intervention as like the payload for a space expedition. It will, of course, be immaculately well designed to its job upon arrival at the destination. But it can’t do anything until it’s delivered to the destination. For transport, an equally well-engineered vehicle is needed, and for ABA interventions, that vehicle is active dissemination.

Every intervention needs a vehicle to transport it to where it can do some real good. The “payload” here is the seven-dimension framework of ABA as depicted in Figure 1 of Critchfield & Reed (2017). The vehicle consists of active dissemination efforts that extend beyond telling other behavior analysts how great the intervention is.

Because interventions are functionally inert until they are implemented, Ronnie and I propose making dissemination the eighth defining dimension of ABA. Our thesis is that if you do everything right according to the first seven dimensions, you can end up with a very promising intervention. But that intervention does not count as truly applied until it is actively disseminated and adopted widely enough to do some world-changing.

Our paper discusses some of the things that need to change in ABA to respect this 8th Dimension, of which I’ll briefly mention three.

World-Changing Outcomes

“What works” is in the eye of the beholder, and the outcomes that impress everyday people may not be the ones behavior analysts favor. Lovaas (1987) understood this and was careful to show that his early-intervention program raised IQ scores and improved school placements. Neither of those things is a behavior, of course. But potential adopters (parents and school personnel) care a lot about them.

In developing and validating interventions, we must go out of our way to track general outcomes. Skim the pages of ABA journals and you’ll see that currently we don’t often do this. Skim manuals on behavioral research and you may even be told not to traffic in non-behavioral measurement. But if we want to impress everyday people with what behavioral technology can do, we have to be ready to show that it makes a difference in ways they understand.

Scaling Up

In the event that someone should adopt one of our interventions, it’s critical that upon implementation it actually be the better mousetrap that we promise. Note, however, that the kind of effectiveness evidence preferred by behavior analysts doesn’t necessarily demonstrate this. This is two problems really. First, effectiveness evidence in ABA typically tests whether an intervention works better than doing nothing, not whether it works better than existing practices that it is designed to replace. Second, as tested in traditional ABA research, interventions often require staffing and resources that aren’t available in the field, especially when we’re talking about wide-scale implementation (“scaling up”). As a result, what the validation research says will work may be pretty different from what is required for good results after adoption. This is something to be thought through as the intervention is originally being developed.

If it’s not properly thought through then the likely result is the “scale up effect,” in which efficacy drops as the intervention becomes widely implemented. At right is an illustrative example (adapted from Araujo et al. (2021; in the excellent book The scale-up effect in early childhood education and public policy: Why interventions lose impact at scale and what we can do about it). A small-scale (N = 64 children) parent-support program in Jamaica produced good gains in child developmental outcomes. It was then replicated in Columbia (N = ~700) and Peru (N = ~70,000), but with depressingly watered-down results. As Ronnie and I discuss, the cause of the scale-up effect might not really be intervention size but rather modifications made to adapt the intervention to its adoption environment. Avoiding this problem begins during the design and testing phase, and requires designing an intervention, not around abstract “best practices,” but rather to reflect what can work well enough within the constraints and resources of the future adoption environment. For more on this critical distinction, see our essay and Fixen et al.’s (2019) Implementation science and practice.

Effective Sales Pitch

It goes without saying that since most people are not behavior analysts, to get our stuff adopted at scale we will have to do a lot of educating. This means communicating directly with potential adopters according to a commonsense verbal behavior analysis that matches our speaker behavior to listener-adopter verbal repertoires. Different types of adopters require different types of dissemination efforts, and there are many kinds of adopters, all with different values, goals, perspectives, and levels of understanding (e.g., parents, school personnel, local officials, business leaders, agency administrators, policy makers, etc.). In all of these cases we must use words that inspire to explain in engaging ways, perhaps relying less on hard data (which rarely excites) and more on well-established tools of persuasion like social influence and good story-telling (check out our paper for more on all of this). None of this can be just made up on the fly. We need replicable technologies of dissemination, and to shape them we need very different kinds of research programs than traditionally have merged out of ABA.

Creating Change

The big picture: It’s time to stop pretending that seven dimensions of ABA are enough. The vehicle designed by Baer et al. (1968) has had a very extended test drive and, regarding the adoption of behavioral solutions at scale, the result has been a bumpy ride. Sixty years of structuring ABA around only seven dimensions did not reliably make most of the world a better place — and you know what they say about the definition of insanity (see Postscript 3).

With a nod to the good folks who are already engaging with 8th Dimension problems — Kudos! We need to learn from you! — it’s time for our discipline to put those problems front and center, to give them the same kind of attention as ABA’s other seven dimensions. Among other things that means we must:

- Make 8th Dimension goals and techniques a foundation of behavior analysis education, including by updating ABA textbooks and standards for certification and accreditation

- Create research programs on 8th Dimension problems that are as systematic and rigorous as those guided by the original seven dimensions

- In professional reward systems, grant the same status to 8th Dimension accomplishments as to more traditional successes

- Rejigger peer review in behavior analysis journals to demand more emphasis on 8th Dimension issues (and, no, Wolfian social validity data are not sufficient)

Fake It Till You Make It

The change we need cannot happen overnight, because what all goals of good dissemination have in common is that we behavior analysts don’t yet know enough about how to accomplish them. But that’s the point of proposing a firm 8th Dimension: To hold our collective feet to the fire to find out how (Postscript 4). Dissemination is an exercise in behavior change, but like all behavior-change endeavors we won’t get good at it until we plunge in, work our butts off, and follow what effectiveness data tell us. At first we’ll make lots of mistakes and have a low batting average of successes, but that’s okay. One thing Baer, Wolf, and Risley (1987) got very right is that, “Failures teach,” because when you fail that means you’re trying. Trying means emitting behavior that can be shaped by consequences.

For role models of plunging right in, look no further than the first generation of applied behavior analysts, who in developmental centers and psychiatric hospitals and prisons faced down behavior problems that were thought to be intractable. One of my favorite things in the entire history of behavior analysis is Ted Ayllon’s initial take (recorded in Alexandra Rutherford’s 2009 book, Beyond the Box) on using principles derived from animal research to enhance behavior of people who society regarded as beyond help. His reaction (paraphrased):

I didn’t think it would work, but I figured I might as well see for myself.

The first applied behavior analysts had no pre-defined solutions to guide them. They tried something, and they tried something else, and they kept trying until they could reliably make good things happen. The reason we are able to help people with autism today, the reason so many practitioners are in demand, is that ABA’s founders were open to making mistakes on the way to making fewer mistakes and eventually getting really skilled at behavior change. So should it be with the behavior change effort called “dissemination.”

Changing the world, as behavior analysts love to say they can do, demands dissemination and implementation on a scale not imagined in a seven-dimension formulation. When 8th Dimension activity finally is woven into everything we do, our discipline may look a bit strange to us, because we’ll need to evolve in order to meet new goals. Which is perfectly fine, because, as Skinner assured us in The Shaping of a Behaviorist, “No practice [is] immutable. Change and be ready to change again.”

Postscript 1: Links to articles in Perspectives on Behavior Science‘s special issue on Challenges to Applied Behavior Analysis.

Postscript 2: The Elephant Graveyard of Effective Interventions

As I was writing this blog there emerged a listserv conversation about all of the promising work behavior analysts have done with education, tracing back to the 1960s and 1970s. If you look at the accumulated evidence, it’s true that we have shown how instruction can be improved. But in the U.S. at least, when you examine the societal-level big picture, it’s obvious that this work has had little measurable impact. Way back in 1983, a report called A Nation At Risk revealed that U.S. students were lagging behind those of many other countries. This elicited quite a panic from a nation in the throes of Cold War era insecurity, an in the ensuing decades countless public policy initiatives have been launched to try to bolster the educational system. Yet today U.S. students are no better off. When you look at the most common policy initiatives (e.g., giving schools more money, reducing class sizes, letting parents choose their kids’ schools, holding schools accountable through high stakes standardized testing, etc.), they tend to have nothing to do with the process of instruction, much less behavioral approaches to instruction.** And as you might expect, they create little change in academic achievement.

My point: All of those great studies on behavioral education didn’t create a societal splash because their innovations were not adopted at a societal level. Whatever else we might say about the accumulated science on behavioral education, from the perspective of students educated 1960 to the present it’s as if that work never existed.

**Caveat: I’m talking about instructional interventions here. Behavior management interventions (e.g., Good Behavior Game, Positive Behavior Supports) have better success gaining a toehold in the mainstream.

Postscript 3: Same as it Ever Was

Sadly, the core issues being discussed here are not new. Check out this plaintive observation that appeared 34 years ago in Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. It highlights how we’ve clung to a model of ABA that clearly was never destined to create wide-scale adoption, and that we’ve known for quite some time it does not.

Ideally, a new technology, directed at a social problem, would first be developed and shown to be effective in an applied setting; the generality of that effective technology would then be demonstrated; finally, the technology would be applied on a large scale…. In practice, technologies developed by applied behavior analysts have not been widely adopted… at any level….. Rather, many imaginative technologies have been developed, addressed to an increasing array of pressing social problems; some of these have been shown to be effective, and a few have been demonstrated to be generalizable…. Very few have been given the final test of application on a large scale. The technologies mostly lie unnoticed in our ever-proliferating professional journals. (Stolz, 1981, pp. 491-492).

The subtitle of Stolz’s article: “Does anybody care?” Um, we should.

Postscript 4: Contingencies Work

For what it’s worth, the first seven dimensions of ABA were proposed prospectively, meaning that in 1968, relatively few applied behavior analysts were doing business this way. In his obituary of Montrose Wolf, Todd Risley (2005) explained how Wolf, as JABA’s first Editor, had to contend mostly with “abysmal” articles, as little that was submitted fully squared with the seven-dimension framework that served as the journal’s mission statement.

Wolf was an unnamed coauthor of half the articles in the first two volumes as he helped authors reanalyze and rewrite their reports to salvage any parts of any work in which measurement and design allowed even tentative conclusions. (p. 284)

But what do you know? Contingencies work! When hewing to the seven-dimension framework became mandatory, people quickly learned.

Within 2 years, submissions of good research increased as people began to do field experiments with adequate measures and single subject designs. (p. 284)

This strategy, of declaring how things need to be, and prodding one another to somehow get there, paid off for ABA once before. It can work again.

THEME MUSIC A

There is a dimension beyond that which is known to behavior analysts…

a dimension of dissemination as vast as space and as timeless as infinity.

— Rod Serling’s “Twilight Zone” opening credits (paraphrased)

THEME MUSIC B: For Those Who View Wishful Thing As a Tool of Dissemination

Pingback: Out of Sight, Out of Mind… But Not Out of the Reach of Operant Contingencies – BEHAVIOR ANALYSIS BLOGS

Pingback: Out of Sight, Out of Mind… But Not Out of the Reach of Operant Contingencies – BEHAVIOR ANALYSIS BLOGS