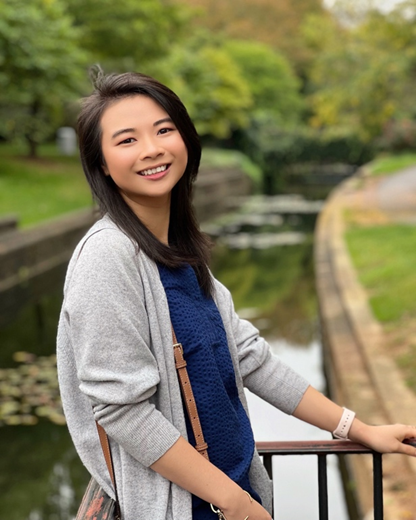

Guest Blog Authored by Xuehua “Shirley” Zhao

Xuehua “Shirley” Zhao is a fourth-year doctoral student in the Applied Developmental Psychology program at the University of Maryland, Baltimore County (UMBC). She earned her bachelor’s degrees in Biological Sciences and Psychology and her master’s degree in Applied Behavior Analysis from UMBC. While completing her master’s training, she worked at the Kennedy Krieger Institute in the Pediatric Feeding Disorders Program. Having lived across multiple continents and within culturally diverse communities, her experiences have shaped her interest in culturally responsive practice and research. Her research focuses on language development in children with autism, with particular attention to bilingual language learning.

Why Culture Matters in Behavior Science

Applied Behavior Analysis (ABA) is often described as a natural science of behavior, focusing on observable actions, environmental contingencies, and functional relations (Cooper et al., 2020). Yet behavior does not occur in isolation. Every learner, family, clinician, and researcher brings a unique cultural context that shapes values, communication styles, expectations, and interpretations of behavior.

Cultural responsiveness and sensitivity are not optional add-ons to ethical practice or rigorous research—they are essential. Attending to culture ensures behavior-analytic work is socially valid, effective, and equitable (Fong et al., 2016; Wolf, 1978). Misunderstandings about cultural norms can lead to inaccurate assessments, ineffective interventions, strained family relationships, and research conclusions that do not generalize beyond narrowly defined samples. For practitioners working with children and families, and researchers striving for broad applicability, cultural awareness is both a scientific and ethical responsibility (Behavior Analyst Certification Board, 2022; Fong et al., 2017).

Defining Cultural Responsiveness and Sensitivity

Cultural responsiveness is an ongoing, reflective process in which practitioners and researchers actively recognize, respect, and integrate clients’ and participants’ cultural identities, values, histories, and lived experiences into their work (Beaulieu & Jimenez-Gomez, 2022; Fong et al., 2016; Jimenez-Gomez & Beaulieu, 2022). In ABA, this means acknowledging that definitions of problem behavior, caregiver goals, communication styles, reinforcement preferences, and social norms are shaped by culture, rather than universal standards. For example, limited eye contact or reduced verbal initiation may reflect culturally appropriate communication rather than social deficits, and families may prioritize cooperation or group participation over individual independence.

Cultural sensitivity is closely related but distinct. It is not about memorizing facts or relying on stereotypes. Instead, it involves humility, curiosity, and collaboration with families and communities (Fong et al., 2016). A culturally sensitive practitioner asks caregivers for input when setting goals rather than assuming that normative developmental milestones are universally valued. From a behavior-analytic perspective, culture can be understood as patterns of behavior shaped and maintained by social contingencies over time (Skinner, 1953). Attending to culture aligns with ABA’s conceptual framework and is essential for socially valid, effective, and equitable practice and research (Wolf, 1978).

Cultural Responsiveness and Sensitivity in Clinical Practice

High-quality ABA services integrate cultural responsiveness and sensitivity to foster trust, relevance, and better outcomes for diverse clients (Beaulieu & Jimenez-Gomez, 2022; Wright, 2019). Culturally responsive practice begins with the clinician. Practitioners must reflect on their own cultural identities, assumptions, and biases, considering how these influence assessment, goal selection, and interactions with families (O’Neill et al., 2023; Wright, 2019). For example, a clinician may naturally value vocal communication or direct eye contact, but in some families, quiet behavior or indirect eye contact is a sign of respect. Regular self-reflection, supervision, and continuing education on diversity, equity, and inclusion help clinicians adjust their practice (Beaulieu & Jimenez-Gomez, 2022; Li et al., 2023). Reviewing session videos can reveal if prompts or reinforcement strategies favor behaviors valued in the clinician’s own culture, allowing adaptations in collaboration with supervisors and families. For instance, praise may be delivered through subtle gestures, nods, or culturally meaningful verbal affirmations. Cultural humility emphasizes that learning is ongoing, and clinicians can strengthen trust and social validity by asking families questions such as, “Are there ways you usually teach this skill at home?” or “Are there routines or traditions we should consider when teaching this goal?”

Families are experts on their children and cultural context, making collaborative, family-centered goal setting essential. Culturally sensitive clinicians listen carefully, ask open-ended questions, and validate family perspectives. Culturally responsive clinicians then adapt goals and teaching strategies to focus on skills that matter most to the family and fit naturally into daily routines. For example, families with limited time may benefit from integrating skill practice into routines they already follow. Research shows that such bidirectional collaboration enhances trust, engagement, and treatment outcomes (O’Neill et al., 2023; Taylor et al., 2019).

Behaviors can carry different meanings across cultural contexts. Quiet or reserved behavior may reflect respect in one culture but appear as disengagement in another. Culturally responsive assessments involve consulting caregivers about culturally normative expectations, avoiding deficit-based language, and considering family routines and community norms (Dennison et al., 2019; Fong et al., 2016). Asking questions like, “How would this behavior typically be understood in your family or community?” helps ensure interpretations and interventions are relevant, respectful, and meaningful.

Interventions are most effective when aligned with family priorities and cultural norms. Clinicians can incorporate culturally meaningful songs, games, or routines and adjust reinforcement methods to reflect family preferences. Focusing on group or family goals, like getting along with others, can be just as important as teaching individual skills. Flexibility in intervention design ensures strategies are meaningful, culturally respectful, and feasible for families (Dennison et al., 2019; Fong et al., 2016).

Finally, communication plays a crucial role in culturally responsive practice. Language shapes how clients and families experience services, and using person-centered, culturally appropriate, and non-stigmatizing language demonstrates both sensitivity and respect (American Psychological Association, 2020). For example, rather than labeling a child as “noncompliant,” clinicians might describe behaviors as “following family norms.” For instance, one could say, “Kai prefers to finish what he is doing before moving on, which aligns with his family’s routine of allowing children time to complete tasks,” instead of, “Kai is noncompliant during transitions.” Or, instead of noting, “Sofia refuses to participate in circle time,” a culturally responsive description could be, “Sofia tends to stay quiet during group activities, which matches her family’s practice of encouraging listening before speaking.” By checking in with families about their language preferences, clinicians can avoid misunderstandings, build trust, and reinforce a culturally responsive approach.

Cultural Responsiveness and Sensitivity in Research

Cultural responsiveness and sensitivity are just as important in research as they are in clinical practice. Inclusive research design, recruitment, and dissemination help ensure studies are relevant, meaningful, and generalizable to diverse communities. Historically, research has often relied on homogeneous samples, which limits its applicability across cultures and contexts (O’Neill et al., 2023; Schimmelpfennig et al., 2025). Researchers can take several practical steps within their own studies to make their work more culturally responsive and sensitive.

One important step is inclusive participant recruitment. Simple adjustments, like offering flexible scheduling, providing materials in multiple languages, or allowing remote participation, can make studies accessible to families who might otherwise be excluded due to work schedules, transportation, or language barriers (Dennison et al., 2019; Fong et al., 2017). Clearly explaining the study’s purpose and benefits in straightforward, culturally respectful language can also help families feel comfortable participating.

Another key area is making research measures and procedures culturally meaningful. Researchers can ensure that the behaviors they measure are relevant to the child’s daily life and family context. For example, when teaching bilingual children, researchers can let families choose words that are meaningful at home, record correct pronunciations, and incorporate routines the family already uses (Zhao & Cengher, 2025; Zhao et al., 2025). Similarly, if studying social behaviors, researchers can account for cultural differences in eye contact, verbal initiation, or ways of showing respect, rather than assuming the same behaviors have universal meaning.

Small changes in data collection and reinforcement methods can also make a difference. For instance, researchers can use preferred items —such as pan dulce (sweet bread) or plantain chips—or culturally familiar activities as reinforcers, observe behaviors in multiple settings to capture the child’s typical responses, or collect input from caregivers about what behaviors are socially meaningful in their context. These adjustments help ensure the study reflects the child’s real-world experiences and values.

Finally, interpreting and sharing results with cultural context in mind strengthens research impact. Reflexivity—considering how the researcher’s own background might influence interpretation—prevents deficit-based conclusions (Finlay, 2002). For example, in a study on conversational skills, a researcher might observe a Latinx child who frequently pauses to confer with siblings or family members before answering questions. Reflexivity helps the researcher recognize that this behavior reflects culturally valued collective decision-making and family-centered communication, rather than a lack of language skills or social engagement. Even small details, such as selecting pseudonyms or aliases for publication, should be handled thoughtfully. Choosing names that respectfully reflect a child’s cultural background—rather than defaulting to culturally mismatched or stereotypical names—demonstrates attention to identity and representation. Sharing findings in accessible ways, such as translated summaries or visual handouts, and describing cultural factors as relevant contextual variables, ensures that research is useful and respectful to the participants’ communities (Fong et al., 2016; O’Neill et al., 2023).

Moving Forward: Culture as a Core Component of ABA

Cultural responsiveness and sensitivity are not trends or buzzwords; they are integral to ethical, effective, and socially meaningful behavior analysis. By attending to cultural variables in clinical practice and research, behavior analysts can improve outcomes for children and families, enhance the credibility of the field, and contribute to a more inclusive science.

It is important to acknowledge that some adjustments—such as flexible recruitment, culturally meaningful measurement, context-aware data collection, or thoughtful interpretation—may not always be feasible due to limited time, resources, or other constraints. Even so, practitioners and researchers should thoughtfully consider which strategies are possible and apply them whenever they can, as even small changes can make practice and research more culturally responsive and meaningful. By making these adjustments when feasible, ABA professionals can conduct work that is scientifically rigorous, respectful, and more relevant to diverse populations.

Importantly, cultural responsiveness is an ongoing process that requires humility, reflection, and a willingness to adapt. As the behavior analysis community continues to grow and diversify, embracing cultural context will strengthen both our science and our impact.

References

American Psychological Association. (2020). Publication manual of the American Psychological Association (7th ed.). https://doi.org/10.1037/0000165-000

Beaulieu, L., & Jimenez-Gomez, C. (2022). Cultural responsiveness in applied behavior analysis: Self-assessment. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 55(2), 337–356. https://doi.org/10.1002/jaba.907

Behavior Analyst Certification Board (2020). Ethics code for behavior analysts. Author

Cooper, J. O., Heron, T. E., & Heward, W. L. (2020). Applied behavior analysis (3rd ed.). Pearson.

Dennison, A., Lund, E. M., Brodhead, M. T., Mejia, L., Armenta, A., & Leal, J. (2019). Delivering home-supported applied behavior analysis therapies to culturally and linguistically diverse families. Behavior Analysis in Practice, 12(4), 887–898. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40617-019-00374-1

Finlay, L. (2002). Negotiating the swamp: The opportunity and challenge of reflexivity in research practice. Qualitative Research, 2(2), 209–230. https://doi.org/10.1177/146879410200200205

Fong, E. H., Catagnus, R. M., Brodhead, M. T., Quigley, S., & Field, S. (2016). Developing the cultural awareness skills of behavior analysts. Behavior Analysis in Practice, 9(1), 84–94. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40617-016-0111-6

Fong, E. H., Ficklin, S., & Lee, H. Y. (2017). Increasing cultural understanding and diversity in applied behavior analysis. Behavior Analysis: Research and Practice, 17(2), 103–113. https://doi.org/10.1037/bar0000076

Li, A., Hollins, N. A., Morris, C., & Grey, H. (2023). Essential readings in diversity, equity, and inclusion in behavior analytic training programs. Behavior Analysis in Practice, 17(2), 523–532. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40617-023-00856-3

Jimenez-Gomez, C., & Beaulieu, L. (2022). Cultural responsiveness in applied behavior analysis: Research and practice. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 55(3), 650–673. https://doi.org/10.1002/jaba.920

O’Neill, P., Magnacca, C., Gunnarsson, K. F., Khokhar, N., Koudys, J., & Malkin, A. (2023). Cultural responsiveness in behavior analysis: Provider and recipient perceptions in Ontario. Behavior Analysis in Practice, 17(1), 212–227. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40617-023-00825-w

Schimmelpfennig, R., Elbæk, C., Mitkidis, P., Singh, A., & Roberson, Q. (2025). The “WEIRDEST” organizations in the world? Assessing the lack of sample diversity in organizational research. Journal of Management, 51(6), 2460–2487. https://doi.org/10.1177/01492063241305577

Skinner, B. F. (1953). Science and human behavior. Macmillan.

Taylor, B. A., LeBlanc, L. A., & Nosik, M. R. (2019). Compassionate care in behavior analytic treatment: Can outcomes be enhanced by attending to relationships with caregivers? Behavior Analysis in Practice, 12(3), 654–666. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40617-018-00289-3

Wolf, M. M. (1978). Social validity: The case for subjective measurement or how applied behavior analysis is finding its heart. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 11(2), 203–214. https://doi.org/10.1901/jaba.1978.11-203

Wright, P. I. (2019). Cultural humility in the practice of applied behavior analysis. Behavior Analysis in Practice, 12(4), 805–809. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40617-019-00343-8

Zhao, X., & Cengher, M. (accepted). Learning-to-learn: A comparison of monolingual and bilingual instruction. Behavior Analysis in Practice.

Zhao, X., Cengher, M., Li. T., Cortez, M. C., & Miguel C. F. (accepted). Bilingualism in children with autism spectrum disorder: Evaluating tact instruction in two languages. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis.