A 20th Anniversary look at an insightful take

on the place of behavior analysis in society.

SECTION COORDINATOR’S INTRODUCTION: OUR GILDED CAGE

Twenty years ago, the inimitable Pat Friman contributed a short-but-prescient essay to an ABAI Newsletter special issue focusing on the future of applied behavior analysis (ABA). That issue arrived at a heady but tumultuous time. Efforts to “professionalize” ABA via certification tied to third-party pay mechanisms had been underway for about a decade, and there was much debate about where this would ultimately lead. In hindsight we know where: Because the professional infrastructure that was taking shape provided financial rewards for delivering autism treatment, this is the direction in which ABA evolved.

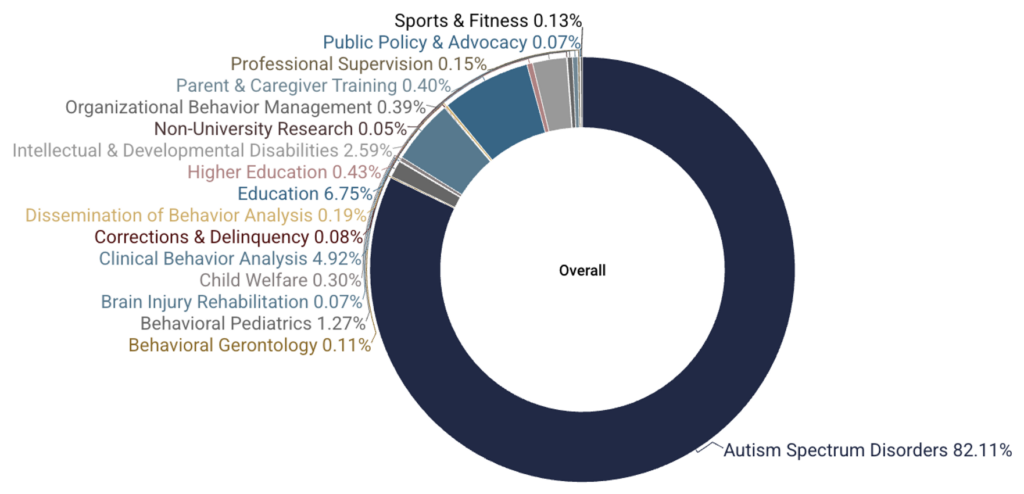

And, holy cow, the professionalization project succeeded beyond anyone’s wildest dreams. As of October 1, 2025, close to 318,000 individuals held certification in ABA! And, due to the dependability of behavior principles, ABA has become precisely what the contingencies favored… a behemoth with limited societal reach. Below, for instance, check out the prevalence of certified behavior analysts working in high-volume mainstream domains of application like education, child welfare, and pediatrics.

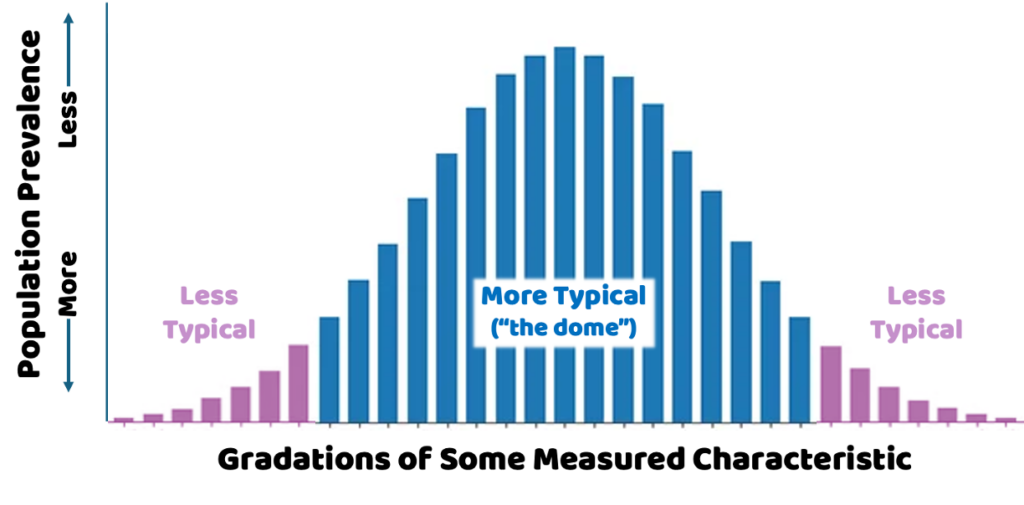

The Friman essay drew attention to a sort of two-marshmallow conundrum for ABA. Assuming the professionalization movement succeeded, effective strategies for autism treatment had already been developed and were awaiting wide implementation (e.g., Rutherford, 2009). Thus, in fairly short order there would be jobs and funding aplenty … in autism. Pat invoked the normal distribution from basic statistics to point out that the rarity of conditions like autism meant that ABA’s powerful tools would benefit a relative few individuals.

Behavioral challenges are not unique to persons woth autism. Typically developing people, those countless individuals under “the dome” of the distribution, also struggle. Think of the mental health conditions that care common among everyday people; the instructional failures of school systems; and the behavioral issues that prevent medical best practices from being widely adopted. Sure, it might take time for applied behavior analysts to figure out how to deal with those challenges, how to implement then, and how to get paid for doing so. But simple math says that ABA’s greatest potential for growth is with problems like these that unfold under the dome.

Pat’s call for ABA to expand its scope is at least as timely today as it was 20 years ago. In 2022, some colleagues and I published a list of 350 different domains of application to which ABA has contributed. Many of these would count as “dome” domains, which sounds like great news, except that, “Our literature search suggested that many … domains have been lightly investigated. For some domains, we found only a single exploratory study or a smattering of loosely related articles. Other domains were explored by a single research team, with their work neither replicated nor extended by other investigators. This kind of breadth-without-depth is concerning because, contrary to the popular notion that science advances through ‘Eureka!’ moments of discovery, progress usually depends on cumulative evidence built up incrementally across many investigations…. Turning [low-attention] domains into large-scale success stories will require considerable additional research” (Heward et al., 2022, p. 339).

In terms of defining domains, remember that not everything that’s of great interest to people “under the dome” necessarily counts as a “problem.” Nothing fascinates human beings like, well, human beings, and they want to understand why humans do the (often mundane) things they do. Curiosities abound. For example, people learn to talk inordinately easily; develop different dialects of the same language; pepper their utterances with curses and non-words (like “um”); and bark out orders that will never be followed. They exchange pleasantries with total strangers; willingly take on obligations that don’t make them happy; and support politicians who are hostile to the very system of governance that grants voters the right to express their support. They see “pictures in the head,” including of things that do not exist (and often are unimpressed with scientific evidence about things that do exist). None of these currently are topics of frequent behavioral research, but a science of behavior that can explain such things can gain the trust and interest of those many voters and taxpayers who reside under the dome.

There’s a further consideration, one that looms larger with each day’s depressing news headlines. Behavior analysts are fond of saying that ABA will one day save the world. But as Mark Mattaini (2006) wrote in the same ABAI Newsletter issue as Pat’s essay: “Essentially all of the major social issues with which humans are currently grappling — global warming, environmental degradation, individual and collective violence, the full range of human rights abuses, even poverty — are the direct result of human behavior and cultural practices…. Applied behavior analysis originated with a concern for ‘issues of social importance.’ And yet… [few] behavior analysts work in these areas” (p. 10). In the realm of human problems, there are genuine “tail” issues and “dome” issues, but the world’s Really Big Problems affect all of humanity. Should the climate betray us or nuclear war erupt, it won’t matter where you happen to fall in that normal distribution.

OK, there’s actually one more “one more thing,” which is that it’s a poor survival strategy for a discipline to put all of its eggs in one application basket. Right now ABA is heavily dependent on autism for its material support, raising the question of what would become of ABA and its hundred of thousands of practitioners if autism were to suddenly cease to be profitable. Same for faculty working in graduate programs that are justified mainly on the basis of a vigorous autism-specific hiring market for program graduates. Right now, autism is the discipline’s Survival Plan A, and there’s no Plan B.

This is simple Panda Logic, folks: If you only eat bamboo, you’re out of luck when the bamboo stops sprouting.

The 350-domain paper mentioned above (Heward et al., 2022) testifies to what ABA is capable of accomplishing, but in each domain of application success is measured in terms of systematic programs of research, careful development and evaluation of solutions, and, most importantly, getting solutions implemented at sufficient scale to enrich a whole bunch of lives (Detrich & Critchfield, 2025). The tone of Pat’s essay was optimistic — We can do this! he seemed to say. And I’m certain we can, but we haven’t, not yet, not really, not at scale in most domains. These days we’ve grown comfortable with an autism-specific version of ABA, to the point that we aren’t even talking much about the agenda Pat laid out for us. For instance, check out Perspectives on Behavior Science‘s 2025 special issue on “Challenges to ABA” in which you’ll find little to no consideration of how to significantly expand ABA’s topical reach, or of what might befall ABA should the wheels detach from its autism gravy train.

There is a lesson to be learned from ABA’s relative success in autism versus, say, traffic safety or martial arts instruction, where very few of us work: Disciplines evolve in ways that professional survival contingencies dictate. Autism is a success story because a lot of people put in a lot of sweat equity to set up contingencies in which a lot of behavior analysts could get paid to help a lot of people on the spectrum. Pat’s essay reminds us that the same must happen in other application domains for ABA to reach its full potential. The essay remains essential reading for anyone who cares about ABA and its potential contributions to a better world.

For a short newsletter piece, “Under the Dome” has been pretty influential. It’s been cited more times than many peer reviewed articles (e.g., see here and here and here), and back in 2018 Derek Reed produced an entire series of posts inspired by it for the Behavior Analysis Blogs (to find those posts just go to the blogs and search “Under the dome”). More recently, many of my own posts have aimed at drawing attention to dome/mainstream issues where behavioral questions need to be answered.

Those of us who read Pat’s essay found that in a very few words it brilliantly framed a key developmental issue for our discipline. Yet because newsletters are ephemeral, a lot of folks have never seen it. Below is a 20th anniversary reprinting (with very light editing, by author permission), offered in the hope that it will inspire someone out there to undertake new adventures under the dome.

— Tom Critchfield

REFERENCES

Mattaini, M. (2006). Trends in social issues. ABAI Newsletter, 29(3), 10-11.

Rutherford, A. (2009). Beyond the Box: BF Skinner’s technology of behaviour from laboratory to life, 1950s-1970s. University of Toronto Press.

The Future of Applied Behavior Analysis

Is Under The Dome

Patrick C. Friman (Boys Town, Omaha, NE)

Reprinted from ABAI Newsletter, 2006, 29(3), 4-5.

Applied behavior analysis (ABA) has flourished under the tails of the normal distribution of human social problems. For example, harnessing ABA to the normalization movements of the latter 20th Century emptied many, and dramatically reduced the populations of most, residential treatment facilities for persons with severe developmental disabilities, thus allowing those individuals a much more normalized life. ABA based treatments have also been successful at reducing or eliminating extreme self-injurious behavior and improving severe deficits in self-care and communication skills in that population. ABA interventions have also significantly increased the velocity of development in children with autism spectrum disorders; expanded food preferences, intake, and self-feeding skills in children with life-threatening feeding disorders; and improved language skills and quality of life in persons with psychotic level mental disturbances. There are many other examples. Such successes represent the power of ABA to help and heal. In many instances, ABA practitioners were the only professionals who would address such problems with non-medical interventions and thus ABA has often been the primary portal from the formerly bleak life of confinement and drastically limited possibilities to an improved life with multiple freedoms and radical optimism for the future for many persons with developmental disabilities and/or severe psychiatric conditions.

But these successes involve extreme problems in extreme populations — those found in the tails of the normal distribution. If ABA has the power to help and heal such extraordinary problems, it certainly has the power to do the same for more mainstream problems that occur under the dome of that distribution. Skinner’s vision of behavior analysis was that it would become a mainstream science relevant to virtually all behavior concerns afflicting human kind. That vision has not yet been realized. However, increased movement towards its realization could be obtained by extending the applications of behavior analysis out from the tails to the vastly more prevalent and less extreme problems under the dome.

A powerful method for facilitating this extension is affiliation of ABA with mainstream social service provision. Schools are a good example. In developed nations, all children go to school and thus ABA affiliation with school systems creates the possibility of expanding ABA services to all children. Over the past 20 or so years, the presence of ABA in the curriculums for training school psychologists has expanded and their roles have expanded too. In some school systems, ABA informed interventions are now being used in school- and even system-wide applications. Although there are limited examples of this, the number is increasing and it represents progress of the sort I am advocating here (e.g., Putnam et al., 2003). Nonetheless, the current role of ABA in education pales in comparison with the role Skinner envisioned in his writings and thus expansion of ABA in education is a key part of the agenda I am advocating.

Another example involves primary medical care. Virtually all persons in developed nations receive it and thus affiliation between ABA and primary medical providers presents and opportunity for extension of ABA-type services to all persons. The examples of such research are limited although they do exist (e.g., Warnes & Allen, 2005). Still, given the societal emphasis that is placed on primary health care, the proportion of ABA-type research devoted to it is best described as infinitesimal.

As a subsidiary example, all U.S. children receive primary medical services and abundant epidemiological evidence shows that primary providers are almost always the first professionals to learn of child behavior problems. Partnership between these providers and ABA professionals could result in behaviorally-oriented interventions being provided at the time of first report, thus producing a heightened possibility of early successful resolution (e.g., Friman & Finney, 2003; Friman & Piazza, 2011). In currently prevailing circumstances, however, most physicians have limited training and time for the delivery of effective early interventions for children with behavior problems, thus leaving the contingencies that produced the problems intact, increasing the probability of deterioration, and often creating a subsequent need for a higher level of care.

Home safety is another topic area that presents an opportunity for behavior analysts to influence mainstream society (e.g., Miltenberger et al., 2005). Unintended injury is one of the greatest threats to health and safety. Such injury often results from environmental-behavioral interactions that, when viewed in retrospect, are almost always seen as having been modifiable to prevent injury. In other words, this area is a logical choice for ABA resources. Another example involves traffic safety. In places with high-volume auto travel, health care statistics are dominated by injury and death resulting from problems at the wheel. Application of basic principles of behavior to the dynamics of road travel could enhance it in a number of ways, including not just accident reductions but also reduced congestion, travel times, and angry interactions among drivers (e.g., Van Houten et al., 2005).

Another example involves expanding the role of ABA in the provision of geriatric services. With the graying of many nations (Lokshin, 2025) has come an enormous number and variety of behavior problems associated with aging including errant driving, dementia, incontinence, medical noncompliance, food refusal, and hygeine, to name just a few. Yet it appears that only a small number of behavior analytic researchers are focused on geriatrics (e.g., Cox et al., 2005; Engelman et al., 2005).

One increasingly successful endeavor to expand ABA to the mainstream involves the general category of community psychology, a field that emerged early in the history of ABA (e.g., Briscoe et al., 1975) and continues to expand (e.g., see any issues of Journal of Organizational Behavior Management). Yet when the scope of the construct referred to as community is considered, the proportion of relevant ABA level interest and endeavors seems disproportionately small, especially in comparison with the interest and endeavors ABA devoted to problems in the tails of the distribution.

There are many other examples of mainstream contexts in which behavior analysis could substantively contribute conceptual and empirical modifications that would produce more effective commerce between persons and their environments. Having said all of this, I do not mean to say that relevant efforts are not being put forth now, as indicated by the illustrative citations above. But the effort put forth in the areas mentioned is typically dramatically less than the effort put forth to address problems in extreme populations. To have a mainstream presence, behavior analysis will have to adapt and increase the number of mainstream applications. In other words, it will have to expand its fortified environments under the tails of the distribution and set up operations under the dome.

REFERENCES

Friman, P.C., & Finney, J.W. (1993). Special section on behavioral pediatrics. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 26(4), 421.

Friman, P.C., & Piazza, C. (2011). Behavioral pediatrics. In W.W. Fisher et al. (Eds.), Handbook of applied behavior analysis (2nd ed.) (pp. 433-450). Guilford.

THEME MUSIC