We are excited to introduce a new blog dedicated to the conceptual side of behavior analysis! Here we aim to explore the philosophical issues that pervade our field, with the goal of understanding the symbiotic relationship between theory and methodology. In other words, our perception of environmental relations dictates our approach to modifying behavior, and – conversely – the outcomes of our experiments alter our perspective.

Perceiving, like all operant behavior, is susceptible to contingencies of reinforcement. As Sidman (1979/2010) remarked, “At issue here is the nature of inference, itself a behavioral process.” (p. 135). The inferential nature of stimulus control will be the focus of our ongoing discussion, as how behavioral phenomena are inferred plays a critical role in shaping the behavioral perspective. Or is it a behavioral perspective?

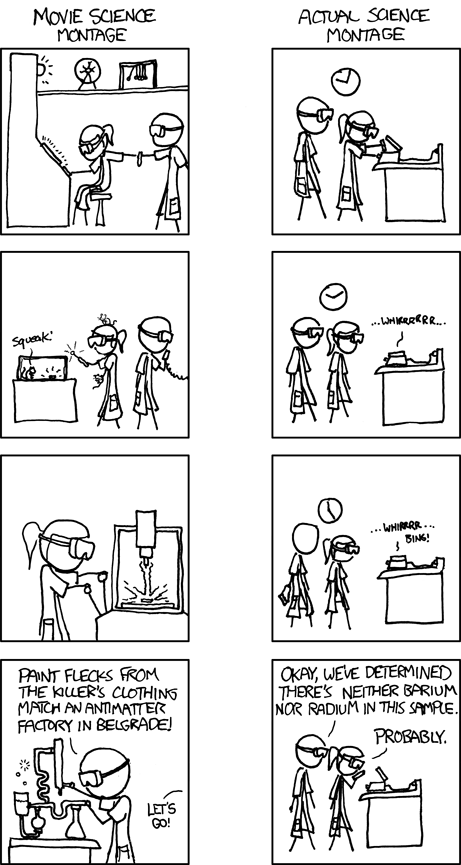

As a natural science, behavior analysis seeks to identify the universal laws and principles that govern behavior. Yet science, itself, is merely the behavior of scientists, each of whom embodies a unique history of reinforcement. Even worse, principles and laws are composed of nothing more than verbal behavior, which — as we have seen over the development of our young science — is highly susceptible to change.

About Behaviorism

When Skinner wrote About Behaviorism just over 50 years ago, he explained,, “What follows is admittedly – and, as a behaviorist, I must say necessarily – a personal view” (1974, p. 8). Skinner’s personal view, radical behaviorism, is primarily concerned with fictional (i.e., dualistic) explanations of behavior, specifically the introduction of mentalistic variables into discussions of causality. Said Skinner (1969), “A radical behaviorism denies the existence of a mental world, not because it is contentious or jealous of a rival, but because those who claim to be studying the other world necessarily talk about the world of behavior in ways which conflict with an experimental analysis” (p. 267).

An initial step in both the construction and deconstruction of mentalisitic explanations is to define your terms. Economist Blair Fix argued that dualism always begins with a definition, which is often represented in terms of a logical equation: phlogiston = fire, income = productivity, magic rock = no tigers. The inherent dualism of such equivalence formations is that we have two dependent variables with one supposedly offering proof of the other.

Skinner (1948) suggested a method to avoid the pitfalls of logical argumentation: “It was not profound; I would simply ask him to define his terms” (p. 9). Once an operational definition has been established, we can devise ways to independently measure both sides of the equation. The distinction between science and logic is that, in science, the definition is followed by an empirical test.

“A radical behaviorism attacks dualistic explanations of behavior first of all to clarify its own scientific practices, and it must do so eventually in order to make its contribution to human affairs” said Skinner (1969). As it increases its power, both as basic science and as the source of a technology, an analysis of behavior reduces the scope of dualistic explanations and should eventually dispense with them altogether” (p. 268).

Mentalisms derail scientific investigation by offering spurious explanations. A classic example comes from Robert Anton Wilson’s Prometheus Rising, in which William James, while giving a lecture about the Earth’s position in the universe, is confronted by a woman who informs him that he is mistaken; in fact, the earth rests on the back of a huge turtle:

“But, my dear lady,” Professor James asked, as politely as possible, “what holds up the turtle?”

“Ah,” she said, “that’s easy. He is standing on the back of another turtle.”

“Oh, I see,” said Professor James, still being polite. “But would you be so good as to tell me what holds up the second turtle?”

“It’s no use, Professor,” said the old lady, realizing he was trying to lead her into a logical trap. “It’s turtles-turtles-turtles, all the way!”

But Wilson warns us, “Don’t be too quick to laugh at this little old lady. All human minds work on fundamentally similar principles. Her universe was a little bit weirder than most but it was built up on the same mental principles as every other universe people have believed in.

“As Dr. Leonard Orr has noted, the human mind behaves as if it were divided into two parts, the Thinker and the Prover. The Thinker can think about virtually anything…The Prover is a much simpler mechanism. It operates on one law only: Whatever the Thinker thinks, the Prover proves” (p. 25).1

Of course, we need not look at human minds to find examples of Thinkers and Provers, as both exist right here in our everyday environment. Though everybody thinks, few exhibit the behavioral repertoire necessary to follow up with data.

Historical Foundations

One goal for this blog is to introduce some of the historical foundations that provide the conceptual framework for radical behaviorism. As part of a recurring series, Michael Passage – Director of the Applied Behavior Analysis Program at Saint Louis University – will lead us on a deep dive through the philosophical foundations of radical behaviorism organized around eight core pillars:

- Naturalism

- Determinism

- Monism

- Materialism & Physicalism

- Empiricism

- Pragmatism

- Selectionism

- Contextualism

Each post will discuss the major figures associated with each pillar within the context of their own historical relationships, influences, and conceptual lineages.

Future Pasts

Importantly, radical behaviorism does not represent the pinnacle of our field’s conceptual development. As research activity in behavior analysis continues to expand and diverge, so do its philosophical orientations. In their book on Contemporary Behaviorisms in Debate, Zilio and Carrara (2021) introduce a variety of behavioral orientations, including teleological, molar, and biological (among others). Throughout this blog, we aim to discuss these, along with other issues of philosophical significance. For example, at last year’s ABAI annual conference, Kenneth James introduced a contemporary spin to William Timberlake’s behavior regulation theory. At last year’s BABAT conference, Jason Bourret argued against the existence of discriminative stimuli. Not to mention ABAI’s entire conference dedicated to theory and philosophy held in Chicago last fall. Clearly, we’re only scratching the surface here. And if you have a philosophical itch to scratch, we invite you to reach out about writing your own guest blog.

Skinner (1969) prophesied that “Behaviorism, as we know it, will eventually die—not because it is a failure, but because it is a success. As a critical philosophy of science, it will necessarily change as a science of behavior changes, and the current issues which define behaviorism may be wholly resolved… There may always be room for a logic of science peculiar to such a science, but it will not deal with the issues which define behaviorism today” (pp. 267 – 268).

Behaviorism is dead, long live behaviorism!

- Orr’s point was that we selectively identify “proof” in support of our theories. A point I am demonstrating here! ↩︎

Across 200 years, Diderot said to Orr, “Unfortunately it is easier and shorter to consult oneself than it is to consult nature. Thus the reason is inclined to dwell within itself.”