Blog Guest Authored by: Marianne L. Jackson, Shaylee Ede, Manal Hussein, and Natalie Longhat

Dr. Jackson holds an MA and a PhD in Psychology with an emphasis in Behavior Analysis from the University of Nevada, Reno. She is a Professor of Psychology at California State University, Fresno, where she directs the Master’s program in Applied Behavior Analysis and serves as Clinical Director of ABA Services. Her research examines complex social skills—including humor and perspective-taking—the motivational functions of verbal behavior, and interventions to promote health and fitness. She has held leadership roles in various behavior analytic organizations, received multiple faculty honors, and secured over $6 million in funding. She regularly publishes and presents internationally, with current humor research among her favorite topics.

Shaylee Ede is a graduate student completing her Master of Arts in Applied Behavior Analysis (ABA) at California State University, Fresno, and is a Board Certified Assistant Behavior Analyst (BCaBA). Her research interests include the behavioral analysis of humor and caregiver-led, trial-based functional analysis with older adults. For her master’s thesis, she is examining the bidirectional effects of multiple exemplar training on the emergence of joke-telling and humor comprehension. Shaylee is deeply passionate about the field of ABA and currently serves in a leadership role within her state organization.

Manal Hussein is a graduate student in the Master’s program in Applied Behavior Analysis at California State University, Fresno. Her current research focuses on using humor-based interventions to increase acceptance of non-preferred foods among children aged 7-10. She works as a Specialized Program Manager and a Senior Behavior Interventionist, gaining experience supporting individuals across a wide range of ages, disabilities, and service modalities. Her professional background also includes staff training in residential facilities, social skills groups, and early intervention services. Manal is deeply committed to ethical, high-quality care and is enthusiastic about continuing to grow in both her professional practice and research.

Natalie Longhat began her professional journey in Applied Behavior Analysis (ABA) during her undergraduate studies at California State University, Fresno. She earned her Bachelor of Arts in Psychology in 2022 and is currently pursuing a Master’s degree in the ABA program at Fresno State. Natalie has gained extensive clinical experience through her work with ABA Services at Fresno State, where she now serves as the administrative manager. Her master’s thesis examines the effectiveness of humor-based interventions with autistic children, with particular emphasis on the role of prerequisite skills. Across her academic and professional roles, Natalie is dedicated to providing high-quality ABA services while fostering a positive, collaborative work environment.

Can We Have a Scientific Account of Humor?

Humor is often viewed as something mysterious, magical, and hard to define. If you ask someone what humor is, you will often get a long list of examples, a description of how it feels, or a shrug accompanied by, “You know it when you see it.” Common properties seem to involve amusement, laughter, and delight, and one of the most influential ideas in humor research is the concept of incongruity (the difference between what is expected to happen and what actually occurs). A good joke often sets up one set of expectations and then pulls the rug from under us with the punchline (Deckers & Kizer, 1975). If you can identify and resolve the incongruity, we might say you “get” the joke. Otherwise, it falls flat. This component of humor is referred to as humor comprehension (how well you understand it) and its companion process as humor appreciation (how funny the joke is to you).

When it comes to measuring humor, researchers often shift from asking what humor is to looking at what people do. Overt responses such as smiling and laughter are often measured by latency to occurrence (i.e., the time from punchline delivery to the onset of the response) and, together with verbal reports of funniness, are used as indices of humor appreciation. Measures of humor comprehension often involve verbal reports explaining why the joke is funny. Of course, a person may be able to explain the source of a joke’s humor and still not find it funny, so it is essential to measure both comprehension and appreciation (Aykan & Nalçaci, 2018).

An additional challenge in studying humor is the common observation that any explanation or analysis inevitably ruins the joke. As E.B. White once said, “Analyzing a joke is like dissecting a frog. You understand it better, but the frog dies in the process” (BrowseBooks, 2025, Humor). This is often taken to suggest that by scientifically studying this subject matter, we are extracting it from the experience itself. Of course, the aim of a scientific study must also address the subtle contextual variables, audience effects, and learning histories that make up the whole experience.

So why bother studying humor at all? The answer is simple: humor matters. In everyday life, having a “good sense of humor” is so valued that it’s earned its own acronym—GSOH—in dating profiles and social descriptions. Humor plays a crucial role in building friendships, attracting partners, and navigating social situations. Research even suggests that humor is crucial for social-emotional development and can help reduce social difficulties, such as bullying (Emerich et al., 2003). Humor also has important implications for health and well-being. It has been associated with reductions in stress and anxiety and improvements in mood, coping skills, and problem-solving. It has even been shown to improve pain management, outcomes of addiction treatments, and immune system functioning (Epstein & Joker, 2007; McGhee, 2010). It turns out that humor is not just a pleasant side effect of social interactions and unusual situations, but can also contribute positively to our physical and mental well-being.

These features of humor as a subject of scientific study lend themselves well to a behavior-analytic approach, specifically an approach focused on the verbal nature of the stimuli involved. Humor is a rich domain of socially mediated behavior shaped by context, history, and consequences. If behavior analysis aims to account for the full range of human behavior, then humor is not only appropriate to study but essential to understand.

What Does Behavior Analysis Have to Say About Humor?

Perhaps unsurprisingly, Skinner laid the foundation for a behavior analytic study of humor in his book Verbal Behavior (1957). He suggested that things could be funny for a number of reasons, from the simplest unconditioned effects of tickling, through the involvement of respondent conditioning, and the reinforcing effects of laughter. Some aspects of these parallel the developmental stages of children’s humor (McGhee, 1971, 2010), with increasing complexity as humor becomes more social and verbal. Skinner advocated for the objective measurement of humor, including a simple count of laughs or a measure of loudness in a large audience. In accounting for humor, he suggested that people may laugh simply because another’s verbal behavior is awkward, unusual, or describes an amusing event. For example, a verbal description of someone slipping on a banana peel (although I’ve never seen this in real life and am not convinced it has actually ever happened outside of the cartoon world) may be almost as funny as actually seeing it happen.

Skinner’s (1957) discussion of humor was more extensive in the area of verbal word play, such as puns, riddles, and jokes. He suggested that humor often arose from a weak verbal stimulus, an unusual figurative relation, or an unlikely intraverbal. Each of these can encourage additional sources of strength to supplement the initially tenuous verbal stimulus. The effect of these multiple variables alone does not ensure laughter or amusement; they must, of course, interact with the listener’s repertoire. He also noted that humor may be used to address otherwise taboo subjects and to allow the speaker to mention them without risk of punishment. It can be socially acceptable to say something outrageous and possibly offensive as long as you do so in a way that amuses and entertains the listener. More than half a century later, Skinner’s analysis remains a valuable framework for understanding humor – not as an abstract mental event, but as behavior shaped by consequences and informed by an examination of stimulus control, thematic variables, and the role of the listener.

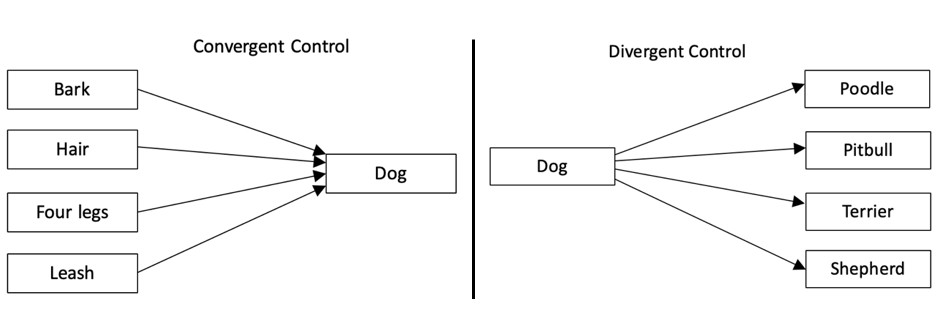

Since then, a few others have expanded upon Skinner’s account. Michael et al. (2011) elaborated on the effects of multiple variables on a number of interesting verbal phenomena, including humor. Multiple control was initially described by Skinner (1957) as occurring when a single response results from more than one variable and when one variable affects the strength of more than one response. Michael et al. described these effects as divergent and convergent control, respectively (see Figure 1).

Figure 1

Example of Convergent and Divergent Control

Note. Multiple stimuli (features of dogs) exert control over the single response dog, and the single stimulus dog evokes multiple responses (types of dogs).

Michael et al. (2011) elaborated on the effects of multiple control on a listener when a joke is delivered, specifying the role of the critical response (the part of the joke with a double meaning), the carrier source or mode of delivery (e.g., spoken, written, pictorial), the main thematic source (listener’s learning history that relates the critical response to the context of the joke), and secondary sources (these also strengthen some part of the critical response but may be included more for amusing or distracting effects that help the listener to “get” the joke). For example, in the joke, “How do you make an octopus laugh? Give it ten tickles,” the phrase “ten tickles” is the critical response as it has formal similarity to tentacles and tickles. This joke could be delivered in a vocal or written format, although it is probably best delivered vocally, as this emphasizes the formal similarity of the critical phrase. The thematic source includes the relation between tickles and laughter, and secondary sources of strength may include the number 10 in the critical response, and its intraverbal relation to eight, which is strongly related to an octopus. The authors also pointed out that primary and secondary control sources are often in competition with each other, and that secondary sources can make the difference between a joke that evokes a laugh or smile and one that evokes a groan.

Differences in the strength and timing of competing sources of control for the listener are also essential features of how jokes produce their effects. Epstein and Joker (2007) described these timing variables and their relation to the perceived funniness of a joke. Their account begins by pointing out that the setup of a joke functions as a motivating operation, a stimulus or condition that alters the reinforcing value of a particular consequence and strengthens behaviors that have resulted in that consequence in the past (Laraway et al., 2003). The setup strengthens several covert verbal or perceptual responses to a level that is insufficient to evoke any particular meaningful response on the part of the listener. The punchline provides additional sources of strength, bringing some of these previously strengthened responses to a threshold where they participate meaningfully in the listener’s response. As an alternative to mainstream incongruity theories, which suggest that the setup leads the listener in the wrong direction so that the punchline surprises them, Epstein and Joker’s approach suggests that the setup prepares the listener somewhat for the humor response, while keeping supplementary sources of strength to a necessary minimum until the punchline, at which point they come together with the listener’s learning history and result, hopefully, in the humor response. The timing with which the listener makes contact with these additional sources of strength, will determine the funniness or humor appreciation; if you derive the additional sources of strength before the punchline (i.e., they are too obvious) it may not be funny, and if you do not contact all the necessary supplementary sources of strength even after the punchline has been delivered (i.e., it has to be explained to you), it may not be funny

Stewart et al. (2001) elaborated on the derived sources of strength in terms of patterns of relational responding known as relational networks. They argued that the setup of a joke was a relationally complete and coherent verbal network (i.e., it made sense initially), but that the punchline introduced an incongruity that led to the collapse of the previous relational network (i.e., no longer makes sense). This allows additional sources of strength to play a role in the reformation of the relational network in unusual and amusing ways. For example, in the joke “Why was six afraid of seven? Because seven, eight/ate, nine,” the listener can respond to the initial question in silly but coherent ways. The punchline both answers the question unexpectedly (i.e., numbers don’t eat each other) and presents a common intraverbal (i.e., seven, eight, nine). The effects of these additional sources of strength are dependent on the listener having previously learned both meanings of the word “eight” and “ate,” and this allows the listener to relate these in novel and amusing ways. This account was further supported by studies showing that humorous functions can transform through verbal relations and that contextual variables can be manipulated to alter the role of supplementary stimuli and the humorous effect (Bebber et al., 2021; Dymond & Ferguson, 2007).

Taken together, behavior-analytic accounts of humor build on Skinner’s account of multiple sources of control, adding a focus on thematic variables, audience variables, and other sources of supplementary stimulation, all in the context of an appropriate motivating operation, listener history, and timing. As a verbal repertoire that incorporates both speaker and listener repertoires, sometimes in the same skin, humor from a behavioral perspective lends itself to interventions to teach, strengthen, and refine humor comprehension and maximize humor appreciation in ways that allow for the many benefits of humor discussed above.

What Can We Do with Humor-Based Interventions?

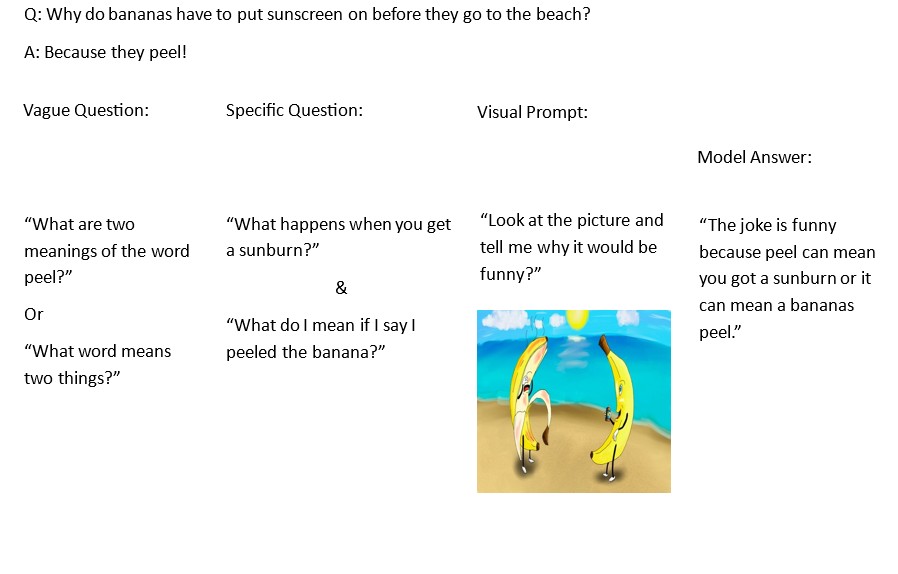

Behavior analytic interventions in humor are scarce (for now), but the possibilities are wide open. In our initial study on this topic, Jackson et al. (2021), we examined the effects of a behavioral intervention on the comprehension and appreciation of double-meaning jokes. Participants were four children aged 5 to 7 (younger than the age at which children typically demonstrate this type of humor), and the intervention presented various jokes, with prompting strategies that strengthened additional sources of control to help them “get” the jokes. To account for the participants’ learning history with each of the main sources of control (i.e., the double meaning), we asked a series of questions, which we called a content-knowledge assessment. This allowed us to select jokes for each participant and ensure that they could respond to both meanings of the critical word or phrase in the joke. We also presented statements or questions that were not jokes to ensure that participants learned to discriminate between jokes and things that are not jokes. We measured participants’ latency to laugh or smile (capped at 10 s), asked them to rate how funny it was on a scale of emoji faces (ranging from not funny to very funny), and then asked them to explain why it was funny or not. The former two were measures of humor appreciation, and the latter was a measure of humor comprehension. The intervention focused on humor comprehension, and if the participant could not explain why the joke was funny, the experimenters first presented a vague question, then a specific question, and then a visual prompt, before finally providing a model of the correct answer (see Figure 2 for an example). All participants in the study demonstrated humor comprehension and appreciation of novel double-meaning jokes with experimenters and peers. In addition, some participants showed small improvements in joke telling.

Figure 2

Example of the Prompting Hierarchy

This study was the first attempt in behavior analysis to teach all aspects of this type of humor and to show that doing so does not, in fact, detract from its effects. It also suggested that we may see improvements in joke-telling (primarily a speaker response) by teaching humor comprehension (primarily a listener behavior), and vice versa. A similar protocol may be useful to teach other types of jokes and to examine broader types of humor. Other unpublished studies suggest that humor appreciation may require more direct interventions (e.g., covert visual imagery), and that specific populations may respond differently to this intervention (e.g., autistic individuals and younger children). Given the widespread benefits of humor, interventions to strengthen people’s understanding and use of humor, in appropriate contexts and with relevant audiences, could yield many benefits. On a more basic level, it will expand the behavior-analytic account of complex verbal phenomena into areas considered crucial to the full range of human experiences. And if you needed another reason to explore humor, from my perspective, it’s the most fun you can have in a lab!

References

Aykan, S., & Nalçaci, E. (2018). Assessing theory of mind by humor: The humor comprehension and appreciation test (ToM-HCAT). Frontiers in Psychology, 9, Article 1470. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2018.01470

Bebber M, Luciano C, Ruiz-Sánchez J, & Cabello F (2021). Is this a joke? Altering the derivation of humor behavior. International Journal of Psychology & Psychological Therapy, 21, 3, 413-431.

Browse Books (2025, December 15th). BookBrowse’s favorite quotes. https://www.bookbrowse.com/quotes/detail/index.cfm/quote_number/435/analyzing-humor-is-like-dissecting-a-frog-few-people-are-interested-and-the-frog-dies-of-it

Deckers, L., & Kizer, P. (1975). Humor and the incongruity hypothesis. The Journal of Psychology, 90(2), 215–218. https://doi.org/10.1080/00223980.1975.9915778

Dymond, S., & Ferguson, D. (2007). Towards a behavioral analysis of humor: Derived transfer of self-reported humor ratings. The Behavior Analyst Today, 8(4), 500–511. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0100636

Emerich, D. M., Creaghead, N. A., Grether, S. M., Murray, D., & Grasha, C. (2003). The comprehension of humorous materials by adolescents with high-functioning autism and Asperger’s syndrome. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 33(3), 253–257. https://doi.org/10.1023/a:1024498232284

Epstein, R., & Joker, V. R. (2007). A threshold theory of the humor response. The Behavior Analyst, 30(1), 49–58. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03392145

Jackson, M., Nuñez, R. M., Maraach, D., Wilhite, C. J., & Moschella, J. D. (2021). Teaching comprehension of double‐meaning jokes to young children. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 54(3), 1095-1110. https://doi.org/10.1002/jaba.838

Laraway, S., Snycerski, S., Michael, J., & Poling, A. (2003). Motivating operations and terms to describe them: some further refinements. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 36(3), 407–414. https://doi.org/10.1901/jaba.2003.36-407

McGhee, P. (2010). Humor: The lighter path to resilience and health. AuthorHouse.

Michael, J., Palmer, D. C., Sundberg, M. L. (2011). The multiple control of verbal behavior. The Analysis of Verbal Behavior, 27, 3-22. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03393089

Skinner, B. F. (1957). Verbal behavior. Appleton-Century-Crofts. https://doi.org/10.1037/11256-000

Stewart, I., Barnes-Holmes, D., Hayes, S. C., & Lipkens, R. (2001). Relations among relations: Analogies, metaphors, and stories. In S. C. Hayes, D. Barnes-Holmes, & B. Roche (Eds.), Relational frame theory: A post-Skinnerian account of human language and cognition (pp. 73-86). Plenum.