Talking the Talk

One of the more pleasant developments in 21st Century behavior analysis is that there’s now wide recognition that it’s counterproductive to tell people about behavior analysis in ways that annoy, offend, confuse, or alarm them. Although this issue has been discussed off and on in our discipline since at least the 1990s (longer if you consider 1970s discussions about how people associate “behavior modification” with brainwashing, drugs, and torture), only more recently has effective communication come to be regarded as a “Duh” issue. You’ve likely seen relevant papers recently in our journals and I doubt many contemporary behavior analysts are against clear and pleasant communication when that will help to gain converts to our cause.

Agreeing on the importance of good communication is not, however, the same as mastering the art of good communication, any more than deciding you’re 20 pounds overweight guarantees a successful New Year’s Resolution. I therefore thought it would informative to size up our collective status quo when it comes to pleasant communication. To do this, I sampled some of what behavior analysts say these days about behavior analysis to see how it measures up on one key dimension of good communication.

That dimension is valence or emotional tone (ranging from negative/unpleasant through positive/pleasant), which matters because considerable research shows that people respond more favorably to positive emotional tones than negative ones. For instance, they find the speaker and speaker’s message more appealing; are more likely to understand the message; and are more likely to pass the message along to other people.

To check out the valence of our talk about our own discipline, I used the online Free Sentiment Analysis tool whose creator, Daniel Soper, explains that, “Sentiment analysis uses computational linguistics and text mining to automatically determine the sentiment or affective nature of the text being analyzed.”

I won’t go into how sentiment analysis is accomplished except to say that under the hood of these processing tools is a lot of computational inference and estimation — if you want more detail, check out an informative explanation of the technical aspects of sentiment analysis, and a nice introduction to how it can be useful in behavioral research, in a 2024 paper by Ian Cero and colleagues in Perspective on Behavior Science. Normally words are not evaluated via actual humans’ responses to them (If you want an example of that approach, see a 2017 article I wrote with Amel Becirevic and Derek Reed). Rather, sentiment analysis judges the words people use more or less in definitional, context-independent terms. Here are some illustrative examples from Cero et al. (2024):

Most English-fluent readers will accurately sense “murder” has a negative polarity that persists across most contexts. Even overall positive phrases like, “I was ultimately glad he was murdered” imply that the typical reaction to murder is negative. This same assumption extends to larger units of speech too. “Not happy” has at least some context free negative valence that persists across the different ways that phrase can be used. Those two words, placed in that order, will tend to imply something negative. The same assumption also extends to word qualities beyond just positive–negative polarity. Words like “bonus” almost always imply some degree of uncertainty or surprise. (p. 287)

The preceding presumably overlaps with how typical people respond, but not necessarily and not universally, so we can’t make any predictions about how an individual listener will respond to the words sentiment analysis evaluates. Still, although sentiment analysis, as a fairly coarse-grained method, is a quick and easy way to estimate how a chunk of verbal behavior might be received by real listeners.

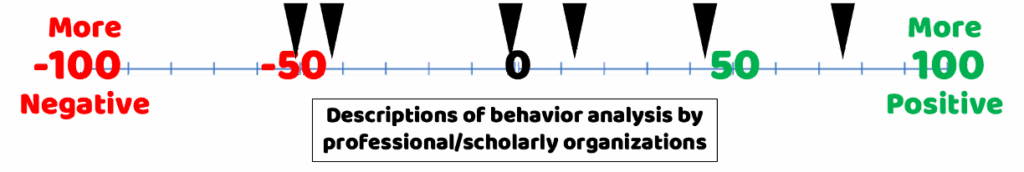

Using the Free Sentiment Analyzer is simple: You paste in a sample of text and it returns a score ranging from -100 (extremely negative emotional tone) to +100 (extremely positive emotional tone). So, what does this kind of analysis tell us about our descriptions of our own beloved discipline?

Walking the Walk?

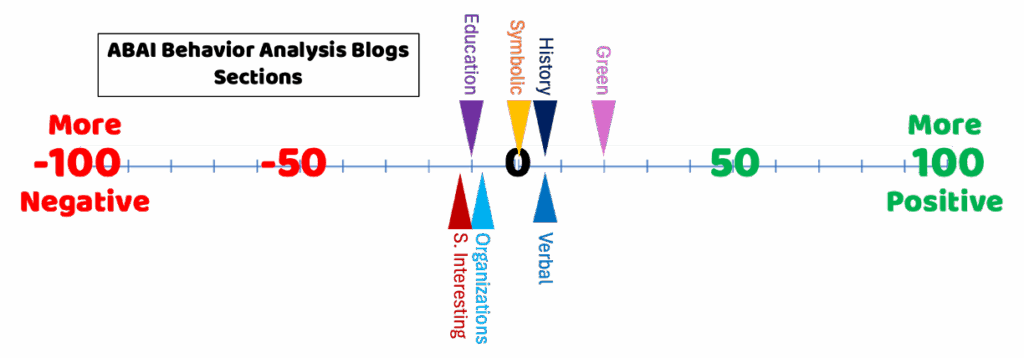

I fed several relevant text samples into the Free Sentiment Analyzer, starting with posts in the Behavior Analysis Blogs. The posts are mostly conversational in tone and we bloggers don’t have peer reviewers holding our feet to the fire to use clunky, and sometimes unpleasant, technical language. We have total freedom to write what we want, how we want. Perfect place to cultivate pleasant communication, right?

Analysis of the most recent five posts in each topical section of the Blogs yielded the average results shown below. The good news: Unlike some previous analyses of behavioral technical language, the posts didn’t register as exceptionally unpleasant. But they didn’t register as terribly pleasant either — more of an emotional “Meh” (with the exception of Green Behavior Analysis posts by the ever-ebullient Susan Schneider). I was humbled to see that the Something Interesting blog — authored by yours truly, who has made something of a cottage industry of demanding better communication — rates rather hypocritically as the worst of the bunch [see the Postscript.].

Okay, that’s interesting. But maybe this isn’t representative of the discipline as a whole — for instance, maybe ABAI has some strange proclivity for choosing curmudgeonly sourpusses to write its blogs. Maybe other folks, especially those who are devoted to the ABA practice community and are forced to interact regularly with regular people, would do better?

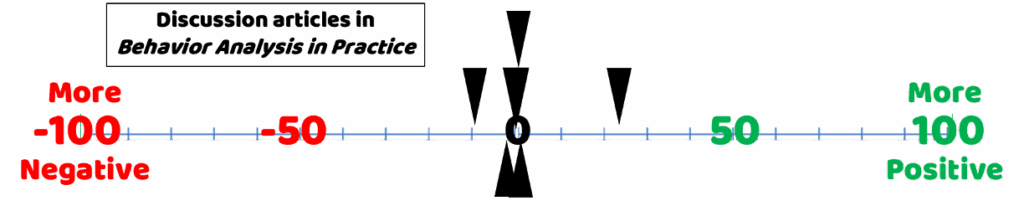

Eh, not so much. I checked some discussion articles [which presumably are less technical than primary empirical reports] in ABAI’s practitioner-focused journal, Behavior Analysis in Practice. Here are the sentiment scores for the first 1100-1300 words of six randomly chosen recent papers.

Now, although the Blogs and BAP probably are less saturated with insider technical language than a lot of what’s written in behavior analysis, they’re still written for behavior analysts rather than members of the public or of other disciplines. Preaching to the choir, as it were, might reduce motivation to employ positive sentiment. So I checked posts in non-ABAI blogs that are focused on the ABA practice world and often aimed at consumers and novices rather than high-level behavior analysts.

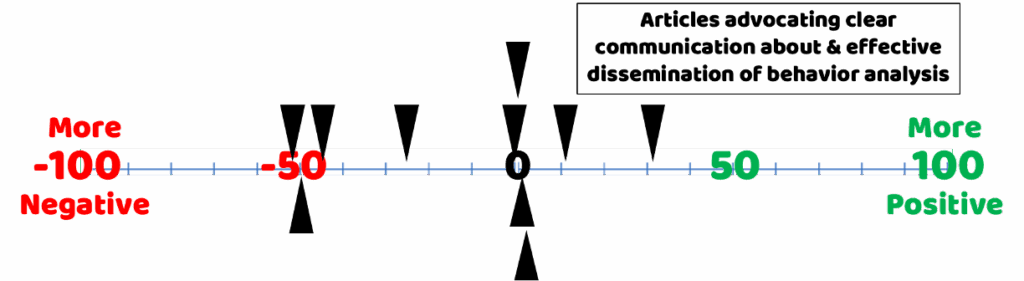

Same story. Next, I sampled a group of behavior analysts from whom you’d expect better-than-typical communication, i.e., people who write articles advocating for behavior analysts to be better communicators. In terms of creating positive sentiment, do they practice what they preach? For each of 10 such papers published 1991-present, I ran the first 1100-1300 words through the Free Sentiment Analyzer, revealing this:

Not encouraging. Also, in keeping with my earlier confession about the Something Interesting blog, you should know that one of these articles is my own. Not saying which one.

For a final exercise, I sampled from the text that various behavior analysis organizations post on their web pages to tell the world about behavior analysis. Since this represents a concerted effort to put a positive spin on the discipline, you might have high hopes for the sentiment of those descriptions, but the actual outcomes are quite varied (see below). If you’re the optimistic type, you might point out that a couple of organizations seem to have cracked the code of positive communication, showing that this is at least possible. But it’s rather surprising that organizations with highly similar missions differ so much in the tone of how they project themselves.

Context and Consequences

Because data are only as good as the analysis that spawns them, at this point you should be asking two questions.

Question 1 is: How do I know ANY of this is truly representative of our discipline as a whole? Because of my relatively small sample of sources, the answer is that you don’t, especially since, with the exception of the Behavior Analysis Blogs, I’m not saying specifically which specific sources (I’m not shaming any individual over what I believe to be a discipline-wide pattern). If you doubt my conclusions, use the Free Sentiment Analyzer or some other sentiment analysis tool to conduct your own tests. See for yourself, and let me know if you find anything that strongly contradicts what I have described.

Question 2 is: What, in terms of sentiment scores, counts as a proper standard for positive communication? I can’t offer a straightforward answer here. The literature is pretty clear on positive sentiment being received more favorably than negative sentiment, but absolute standards (what’s “positive enough”) are tricky. This is true in part because each sentiment analysis tool works slightly differently, and in part because, as far as I’m aware, there are no studies scaling sentiment scores against reliable measures of listener responding (maybe the studies are out there; I just don’t know of any). I’ve seen sources suggesting that the top 1/5 or 1/10 of the sentiment scale is a desirable goal, but how achievable that might be is I can’t say. You’ll notice that almost none of the examples I checked even approximated that standard.

The present discussion is complicated by evidence from actual human listeners showing a baseline asymmetry between positive and negative sentiment in verbal behavior. That is, apparently all languages contain more positive than negative words, and intensely negative words are fairly rare (see here and here). This has two implications. First, because the mean sentiment of verbal behavior overall is somewhat positive, language that scores as nominally neutral might actually be perceived as relatively negative. This places some of the “Meh” results shown above in an even less flattering light than might first be assumed. Second, in everyday language the strongest negativity seems to be reserved for words that describe or are used to issue threat. This places the most negatively-valenced discussions of behavior analysis, as shown above, in sketchy company — roughly on par, sentiment-wise, with words like cancer, murder, and motherfucker. Just spitballing here, but that might not be the public relations magic our discipline is looking for.

And there’s probably more. For instance, my gut tells me that the benefits of positive sentiment probably reflect an inverted-U curve, such that more is better, but only up to point. Communication that’s too positive might be regarded as delusional or untrustworthy. That could be especially true in verbal behavior that’s expected to be be serious and high minded, as per the communication between scientists. For now, however, there’s no evidence that behavior analysts need to worry about coming across as too positive.

As a writer, it’s safest to view sentiment analysis as a relative thing, a prompt to always be on the lookout for more pleasant ways of communicating. As you refine what you have to say, for whatever purpose and whatever audience. you can check tools like the Free Sentiment Analyzer, aim for a more positive sentiment, and then check again to gauge your progress. Of course, all feedback should be taken with a grain of salt. Some tools, like the one I used, provide only an overall assessment of sentiment in a chunk of text. If you paste in a big chunk of text, they do not diagnose sentiment at the level of individual passages, paragraphs, or sentences. Moreover, they do not take into account the likelihood that readers find certain kinds of within-text shifts in sentiment particularly reinforcing. Be aware too that some ways of writing that yield positive sentiment might be incompatible with the type of writing you’re doing. And so on and so on. Writing is a contextual, multi-headed hydra, and sentiment analysis tools are just one means of sizing it up. But if we are serious about presenting our discipline in the best possible light, we absolutely need objective means of sizing up how we communicate.

Postscript

Regarding the sometimes negative tone of my own blog posts: My goal has never been to tell behavior analysts that all is well with the discipline. Behavior analysis needs to grow and evolve in a number of ways, and if describing the Emperor’s scanty wardrobe comes across as unpleasant, so be it. Having chosen that type of message, however, I need to understand that I might be limiting the size of my potential audience.

THEME MUSIC