Preface: During the entire span of my career, behavioristic endeavors have been derided by critics in both academia and the public press as primitive, overly simplistic, or (as in the case of Chomsky’s infamous review of Skinner’s Verbal Behavior) just plain wrong. And that is the better-case scenario. Often behavioral approaches have been portrayed as tools of torture and coercive manipulation, or, as per Bernard Baar’s The Cognitive Revolution in Psychology, as a cancerous force that across many decades stifled the intellectual vigor of psychological inquiry.

But what’s worse than being unfairly criticized? Being treated as if you don’t exist. The end result of decades of derision is that many in the sciences and the general public have moved on from thinking about behaviorism. Although most behavior analysts alive today are too young to have experienced the most virulent direct attacks, we all live with the sequelae: Outside of autism treatment, behavior analysis is little known and rarely utilized.

How we got here is complicated, and in this post I address only a small part of the relevant sociocultural dynamics of science… with a nod to a mostly-forgotten little investigation that, had it been properly appreciated for what it demonstrated, might have been a mouse that roared in the conflict between behaviorism and cognitivism.

It’s said that every intellectual movement has a dragon that must be slain to justify its existence. For early Behaviorism, the dragon was Introspectionism. For Cognitive Psychology, the dragon was behaviorism. Consequently, as the so-called cognitive revolution unfolded, a sense of urgency arose to place cognition at the fore by dispatching behavioristic views.

As has been detailed many places, the early “cognitive revolution” (circa 1940-1950) was much influenced by the assumption that “thinking machines” (computers) provide a model of how human thinking works. Computers “process information,” and this approach assumed the same of humans. A key sticking point was the behaviorist research program demonstrating considerably sophisticated learning, mainly in nonhumans, as a result of no apparent “information” except experience with operant contingencies.

Since information was the presumed currency of the mind, cognitivists posited that humans, when exposed to contingencies, must be generating their own “information.” That is to say, to learn they must become aware of the contingencies, a view that quickly transformed into the hypothesis that (unlike nonhumans, apparently), humans could only learn from contingencies if they were consciously aware of them.

This hypothesis was notoriously difficult to test. For instance, in Greenspoon’s famous experiment, participants were asked to talk, and a listener-experimenter would make noises of approval (“Mmm-hmm”) following plural nouns, which subsequently increased in frequency, purportedly showing reinforcement effects. When interviewed, the participants seemed unaware of this effect or the contingency that spawned it. But arguments arose as to whether awareness was adequately probed, and some replication efforts, purporting to fully eliminate the potential for awareness, did not reproduce the results. The proposed conclusion: “There is no convincing evidence for operant or classical conditioning in adult humans.”

Some people might also point to Paul Fuller’s (1949) famous early demonstration of shaping in a comatose patient, but definitions of “coma” are pretty hazy, and uncertainties exist about how much residual awareness might linger in an unresponsive individual. Thus, it was easy for critics to dismiss this study as not necessarily showing what it claimed to.

Image credit: Alchetron

But lurking in the background was research that demonstrated “learning without awareness” beyond any reasonable doubt. This now mostly-forgotten research was conducted by Ralph Hefferline, and it employed a brilliant setup in which only the stubbornest of critics could argue for some sort of awareness.

Hefferline was an interesting guy. He received his PhD from Columbia in 1944 (where he did some operant research), and went on to join and later chair the Psychology faculty at Columbia. He was better known as a Gestaltist than a behavior analyst, having co-authored an well-regarded 1951 book on Gestalt therapy. But he was also much influenced by Skinner’s accounts of private events and verbal behavior (we know about the latter interest because Hefferline took notes on a 1947 summer course at Columbia in which Skinner presented early versions of what would become Verbal Behavior; distribution of these notes helped to spread Skinner’s ideas in advance of the book’s publication).

Hefferline also had some exposure to biofeedback methods which, when combined with an interest in private events, provided the perfect vehicle for researching the role of awareness in operant learning. Hefferline published a series of studies employing similar methods; here to illustrate I’ll focus on his 1959 report in Science.

Participants were fitted with headphones and several electrodes, one of which could measure extremely tiny movements in a thumb muscle. Noise was played through the headphones, but would temporarily cease when a tiny thumb twitch occurred. Results for the main group are shown at right. In an A-B-A design, thumb twitches occurred in frequently in baseline but increased in rate under the avoidance contingency. Rates decreased when the contingency was suspended.

When queried afterward, these participants claimed to have done nothing to stop the noise. Because they were unaware of making thumb twitches, they could not know that thumb twitches terminated the noise. Learning without awareness.

But maybe the coolest thing about this experiment was the control groups. One was told that some unspecified, unobservable response could terminate the noise. One was told that the critical response was a tiny thumb twitch, and another was told the same and given visual feedback to show when the response occurred. All four groups performed similarly, effectively showing that “awareness” added nothing to the effect of the avoidance contingency.

It would be awesome to say that Hefferline’s research stifled the cognitive critics, tossing the whole awareness-as-prerequisite hypothesis out the window. but that hypothesis hung on stubbornly. More than two decades later Brewer (1974) still asserted

Conditioning in human subjects is produced through the operation of higher mental processes, rather than vice versa.

But over time, ever so gradually, Cognitive Psychology has had to come to grips with mountains of evidence that not everything results from conscious consideration of “information.” Today it’s widely accepted, even in cognitive psychology, that a lot of behavior control traces to processes that are variously described as implicit, unconscious, embodied, automatic, etc. (in other words, outside of conscious awareness).

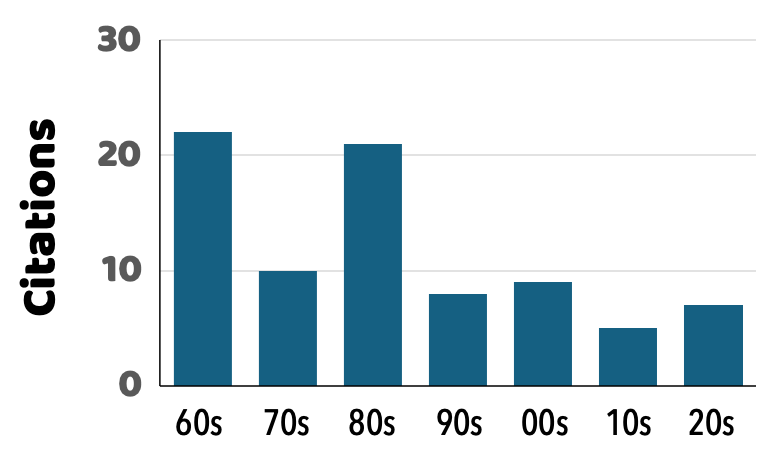

Hefferline’s work stands as a hearty historical “I told you so.” That doesn’t mean it was impactful, however. Web of Science lists only 97 total citations of Hefferline et al. (1959) in the 56 years since its publication. Most of those came early on, and according to my own inspection, almost none come from publications at the epicenter of the Cognitive Revolution.

I used Web of Science to itemize citations of the 1959 paper plus three closely related empirical reports (here and here and here), yielding a total of 174 citations. Of these, according to the Web of science “Citation topics micro” tool, only 10 were in sources with primary focus on basic cognitive processes (e.g., cognitive biases, memory processes, music cognition); another handful represented research areas that tend to have a strong cognitive slant (e.g., visual attention, motor control).

In short, Hefferline’s impeccable evidence that “information” isn’t needed in human operant learning was all but ignored by the scientific movement predicted on the centrality of information processing. Let that sink in for a moment.

Now, we must ask, why didn’t Hefferline’s work didn’t make more of a splash? The answer may say much about the political and cultural dynamics of science. The Cognitive Revolution arose in part because of honest preferences regarding method and theory. But it also created something of a virtue-signaling arms race in which cognitive scientists clambered over each other to show who could pit the most distance between themselves and the dark stain of behaviorism. That, of course, has nothing to do with evidence.

Had the movement been more attuned to solving problems with hard evidence, regardless of its origin, Hefferline’s work should have been of great interest. But it had too many trappings of behavioral research (the language of reinforcement, cumulative records, etc.) to seem relevant or trustworthy to cognitive-science crusaders.

This is not an isolated example. For Cognitive Psychology to qualify as a general purpose account of behavior, it would have to account for all competently acquired data on that topic. But that kind of thing doesn’t happen when you simply ignore the other guys’ efforts. For instance, as far as I’m aware Cognitive Psychology never developed an independent account of Skinner’s great experimental legacy, Schedules of Reinforcement. For cognitive science to be an improvement over behaviorism, as its advocates often proclaimed, it would need to generate a more successful theoretical account of their rivals’ data.

I’d love to continue thumbing my nose at those narrow-minded cognitivists who ignored Hefferline, but the reality is that scientists of all varieties tend to separate themselves into silos, or echo chambers, consisting of colleagues who mostly agree with one another. We’re all attracted to work that aligns with our preferred approach. And work that doesn’t? We all tend to ignore it, while issuing blanket dismissals of its validity, despite having not actually spent much time examining it. Tgat includes behavior analysts, and the “ignoring” part is easy to quantify. For instance, according to Web of Science, only about 2% of the sources cited in articles published by Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior represent core areas of research by our cognitive rivals. For Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, it’s about 1/10th of that. And if you haven’t heard the “blanket rejections” that behavior analysts offer for cognitive work, well, then you haven’t been hanging around many behavior analysts.

Echo-chamber science is not healthy. As Hefferline’s classic investigation illustrates, data are data, and you don’t have to buy a researcher’s theoretical orientation to be informed, or challenged, by them. Sure, the Cognitive Revolution shortchanged itself by ignoring behavioral research data, but it’s equally true that behavior analysts forfeit learning opportunities by ignoring research conducted outside of behavior analysis. Before you can claim that behavior analysis is better than some alternative, you’d better be sure you have a solid explanation for the data accumulated by people representing that perspective.

THEME MUSIC