Getting behavioral technologies integrated into everyday life is so important — to the well being of behavior analysis and to the literal fate of the world — that a previous Something Interesting post proposed making the active pursuit of societal acceptance a defining dimensions of applied behavior analysis. This pursuit is often portrayed as a marketing challenge: If we can just persuade the general public that behavior analysis is good (kind, beneficial, and effective), they will adopt it. But that thinking may be backwards.

Recently, on one of the list servs to which I subscribe, folks were waxing poetic about all of the great work behavior analysts have done in education over the years. They were 100% right to feel good about that stuff, because behavior analysts have devised some profoundly effective ways of supercharging instruction. What few of my nostalgic comrades seemed interested in discussing, however, is how little of a societal splash those wonderful innovations have made. Your typical citizen-on-the-street probably doesn’t even know the technologies exist, and big-picture evidence of their impact is scarce. Here in the U.S. where I live, for instance, schools were mediocre before behavioral education became a thing, and they remain mediocre today. That’s not because technologies of behavioral education weren’t effective. It’s because they were scarcely used.

That might seem odd to contemplate given the current reality in which technologies associated with a different domain of application (autism) are in frantic demand. ABA autism practitioners are being put to work as fast as they can be trained (and these days you know you’ve really hit the big time when you acquire your own community of online haters]. So: We know for a fact that behavioral solutions sometimes can generate considerable public interest.

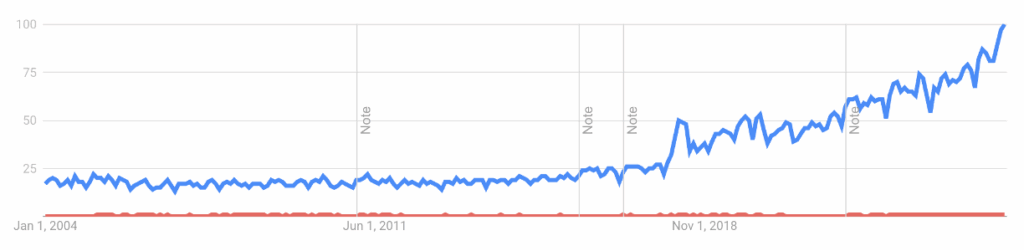

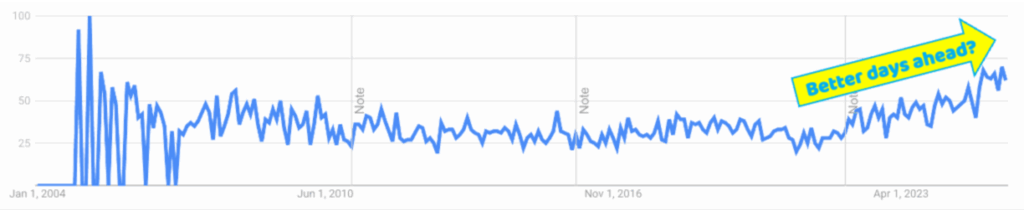

To make a point, let’s quantify some of that interest by looking at Google searches for “ABA autism” as tracked by Google Trends (Postscript 1), which tabulates how frequently people in general seek online information about some topic. Below, the blue function shows how relative search interest in “ABA autism” varied across 2004-2024 in the U.S. You can see that during the past seven or eight years the rate of those searches has been steeply accelerating (Postscript 2). Googlers are paying attention!

But of course the fact that effective technologies can attract public interest doesn’t mean they always will. Above, the red function shows that searches for “ABA education” have occurred at a comparatively miniscule rate across the entire measurement period (Postscript 3). That’s curious right? I mean, the effectiveness evidence supporting behavioral instruction is at least as good as that supporting behavioral autism interventions, and far more people are affected by the education system than by autism services. Logic suggests that there should be considerable public interest in behavioral education. But of course when it comes to evidence-based practices, logic and public interest are at best strange bedfellows.

Chicken and Egg

To make sense of why behavioral education remains in shadow, we can take clues from the history of ABA in autism. Back when I was in school, my chums and I thought fellow students who chose applied work over the professorate were impractical dreamers. Sure, technology they needed to be effective existed, but there wasn’t much societal support for autism services. Many people with autism were shunted off to overcrowded, underfunded, understaffed psychiatric hospitals, so if you wanted to work with them you might find a job, maybe, but those were scarce, and you had to be prepared for squalid working conditions and poor compensation.

Although the ABA juggernaut we know today was forged by a series of events unfolding across a number of years, for present purposes the critical thing is that no “better mousetrap” was involved, because even in the Medieval days of my youth the fundamentals of autism treatment were already pretty well worked out. The change that mattered most was that ABA was made more available.

Everyone today knows that a practitioner certification system was part of the equation, but a credential is meaningless unless someone is willing to pay for the relevant expertise (just ask credentialed behavior analysts in nations where the credential is not tied to third-party pay mechanisms). In the U.S., the critical change involved creating a funding stream for ABA services. A lot of people worked tirelessly with state legislatures and insurance companies to get ABA for autism covered under health insurance. And once that happened, suddenly ABA services were everywhere.

I hope this example subverts the intuitive notion that information changes behavior. For as long as ABA has existed — actually for longer (consider Walden Two and Science and Human Behavior) — we behavior analysts have been telling the world that we can craft solutions to the world’s problems. For just as long, people out there have mostly been tuning us out.

As a verbal community, we sometimes seem to operate under the delusion that knowledge drives adoption — if you just just explain, loud and long enough, people will come around and start to care about ABA. But telling isn’t teaching, and what the case study of autism treatment shows is that you must first make ABA available, and then people will start taking an interest.

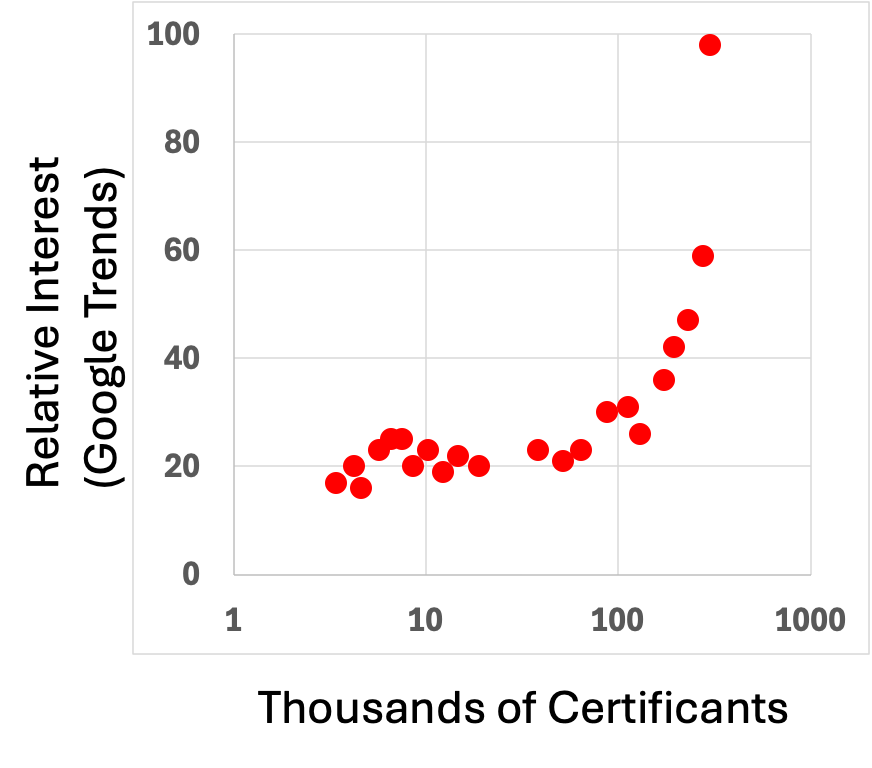

We can see evidence of just this in the Google Trends data. In the graph below, on the abscissa I’ve plotted a measure of ABA’s “rollout volume,” the total number of new front-line professionals (BCBA® + BCaBA® + RBT®) certified each year during 2004-2024. On the ordinate is relative search interest in ABA/autism as measured by Google Trends.

Practitioner certification has increased ordinally every year over the past couple of decades, so in reading the graph from left to right we’re also counting the years from 2004 through 2024 in sequence. Notice that initially, even as the number of available (and affordable, if you had health insurance) practitioners increased, search interest remained fairly flat. But once the number of new certificants per year topped about 100,000, search interest jumped. That’s entirely consistent with the notion that you need a critical “implementation mass” before you gain the public’s attention.

An Exception That Proves The Rule

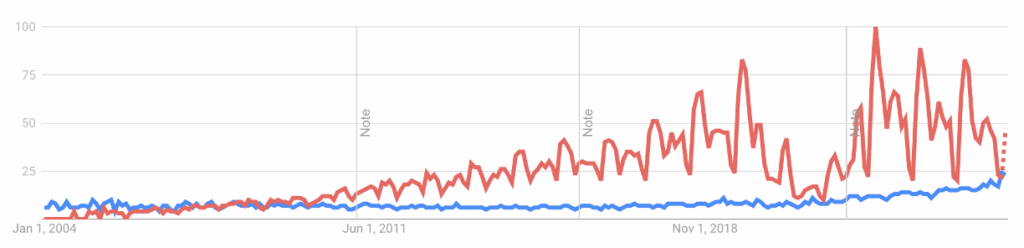

Now here’s a “control condition” to bolster the point that availability/implementation comes first, and public interest second. In the late 1990s and early 2000s, Positive Behavior Interventions and Supports (PBIS; Postscript 4) began to be widely installed in schools throughout the U.S. Today it’s in tens of thousands of schools. Unlike most everything else created for education by behavior analysts, PBIS attracts a lot of public attention. Below, you can see that “PBIS,” in red, absolutely dwarfs “ABA autism,” in blue, in terms of search volume. Notice as well that although widespread adoption began at least ten years earlier, search interest in PBIS accelerated only after about 2010. That’s consistent with the proposition that availability/implementation drives public interest.

The Policy Imperative

And how does adoption at scale come about? Through modifying societal systems. The creators of PBIS first devised technology that was ready for prime time (PBIS was designed expressly to be implemented at scale, i.e., to work seamlessly with existing educational infrastructure). Then, drawing upon the factors that predict adoption of innovations, they worked tirelessly with policy makers at the state and federal levels to promote adoption.

What the two cases discussed here (autism and PBIS) have in common is that adoption was treated as a pubic policy issue. Information wasn’t put out there into the digital void to be discovered by whoever might stumble across it. Rather, key decision makers were the focus of systematic persuasion efforts.

If you want to know more about such efforts, start by reading our own history, paying attention not to the successes per se but rather to the back stories of how those successes were engineered.

For context on those back stories, well, a ton has been written about how the public policy sausage gets made — some by behavior analysts, but most by people who specialize in understanding the policy making process (if you’re just getting started, I recommend Gerston’s (2010) Pubic Policy Making, which provide a concise summary of the relevant dynamics). I won’t delve into specifics here but suffice it to say that you must get the ear of decision makers and understand what their reinforcers are. You also have to live with the fact that people who disagree with you are playing the same persuasive game, so you’re not always going to win, even when you do everything right. But the surest way to fail is not to try (Postscript 5).

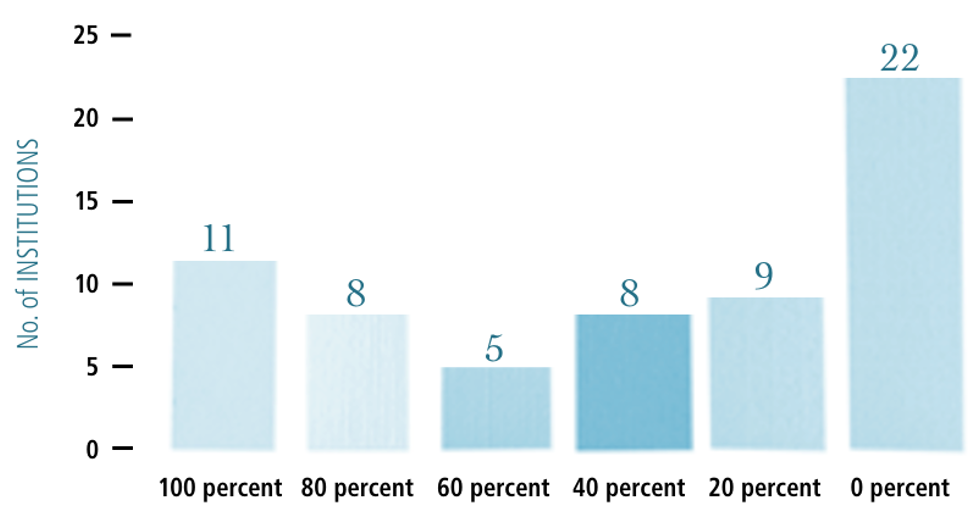

This Is Hard

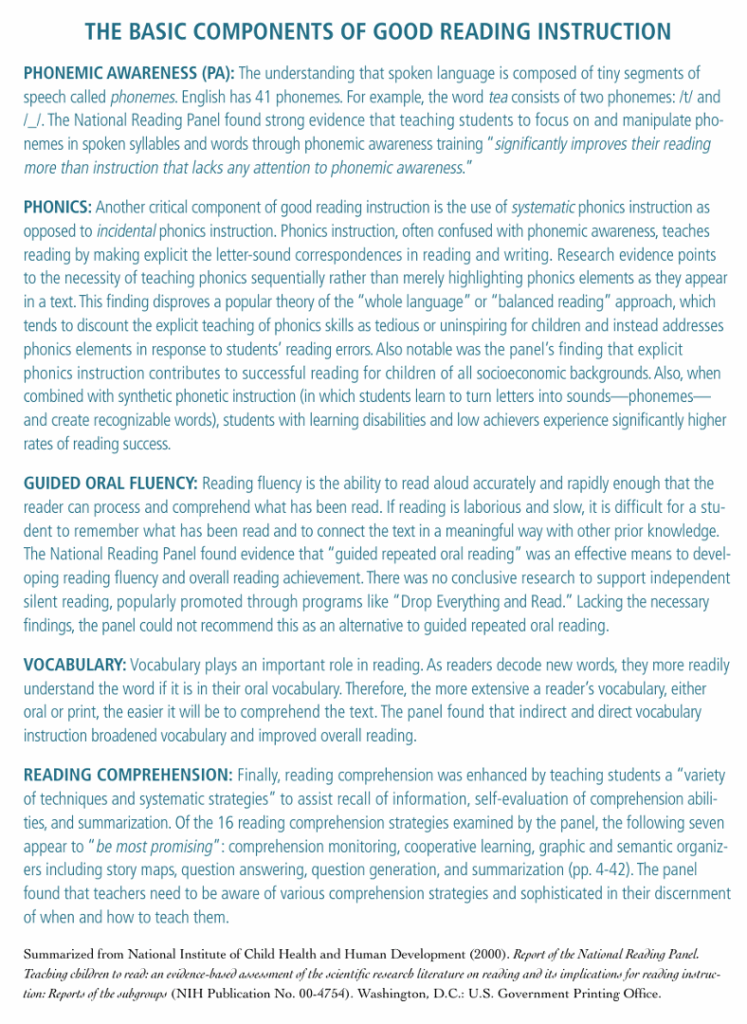

The folks behind PBIS did a great job of gaining the notice and confidence of decision makers, but not everyone cracks the policy-influence code, the relevant challenges of which apply to much more than behavior analysis. For instance, we know that on the whole U.S. students read poorly, so a worthy goal would be to improve reading instruction. There’s a vast literature (some from behavior analysis, but mostly not) that converges on five simple components of effective reading instruction (Postscript 6). The National Council on Teacher Quality (NCTQ) surveyed syllabi at many Colleges of Education to find out how reliably these components were being taught to teacher trainees. The results were dispiritingly awful. Each institution surveyed could score from 0% to 100% depending on how many of the five components were being taught, and as you can see below, the most common outcome was 0%.

Teachers teach reading, so if you want schools to teach reading well, you have to somehow make sure teachers know how. And the most straightforward way to accomplish that is to make sure Colleges of Education teach them how — perhaps, for instance, by making this an accreditation requirement, or maybe by assuring that schools only hire teachers who’ve been certified in effective practices. It would be close to impossible to individually budge each of the institutions that award education degrees. I’m not saying that it would be easy to change the depressing status quo described in the NCTQ report; only that the operative choice is to either live with mediocrity or find a way to influence educational systems.

Shame, But Maybe Not The Kind We Thought

Skinner once wrote a paper called “The shame of American education” in which he correctly noted that:

- The U.S. education system places much emphasis on things like material resources and curricular requirements, but little emphasis on technologies of teaching. (For a somewhat more contemporary take on this problem, see Yeh’s [2007] report showing dismal cost-effectiveness of several popular educational policy initiatives such as smaller class sizes and increased funding).

- One can neither blame students for failing to learn when they haven’t been properly taught nor blame teachers for failing to teach when nobody has shown them how.

- Effective technologies of teaching can solve both problems, making schools a more rewarding environment for students and teachers alike, and giving society citizens who are more capable and productive.

What Skinner didn’t tell us is how to get those technologies adopted by educational systems. I’ve always found that a curious omission, because one of Skinner’s great gifts was insightfully parsing the world’s Big Problems. Well, guess what? Getting solutions to those Big Problems widely adopted is quite possibly the world’s biggest problem. If our way of understanding and changing behavior is truly powerful, then no behavior problem, not even that of getting behavioral solutions adopted, should lie beyond our reach.

Slime Theory

Adoption is behavior, and behavior is orderly. The trick is to identify and harness the variables that influence adopter behavior, precisely as was accomplished for both autism treatment and PBIS.

Those examples illustrate success breeding success, and the triumph of experience over “information.” Implementation creates something that’s entirely unremarkable from a behavior-principles perspective but formidable in its practical implications: reinforcer sampling. Drawing upon the venerated scholarly treatise known as Slime Theory (inset), we can predict that once people get a taste of what effective behavior technology can do for them, they usually want more.

Behavioral work in education has yielded many promising technologies, and I am absolutely certain those technologies can create instructional magic that will dazzle the public… as soon as we figure out how to get them adopted/implemented at scale. But probably not before. For decades we’ve been telling people that we can help their loved ones thrive in school, when the best way to persuade is to show them.

Postscript 1: About Google Trends Data

Google Trends does not provide raw data on search interest, only, for a given topic, how interest has changed over time compared to a historical maximum. Hence the data points are basically percentages of the topic’s best-ever (within the measurement window) search volume. When between-topic comparisons are made, the results for both topics are shown relative to the maximum search volume for the higher-frequency topic. Also, the analysis is based on a random sample of user searches, not every search conducted in Google.

Postscript 2: Not All Attention Is Good Attention

I’m not naive. I don’t think that every person who is aware of ABA has kind thoughts about it. Someones the reason people are interested in us is that they’ve been persuaded we’re a scourge, so of course a careful analysis of public awareness and attention demands diving deeper into what they’re saying about us.

Postscript 3: Regarding Search Disinterest in “ABA Education”

In case you’re thinking this outcome is maybe the result of a clumsy query on my part, I assure you: No matter how you probe Google Trends regarding behavior analytic work in education, you get similar results. Try different general terms (e.g., “behavioral education”), or search for specific types of behavioral technology (e.g., “Precision Teaching,” “Personalized Systems of Instruction, etc.)… no matter. Whatever you enter, you’ll discover that close to nobody is asking about that.

That being said, this is a fuzzy category. There’s a lot of great work in education by people who have behavioristic sensibilities but don’t necessarily identify first and foremost as behavior analysts. Their work wouldn’t have behaviorist labels that would show up in my searches.

Also, for you optimists, I’ll toss out this bone: Here’s an expanded view of “ABA education” searches over time, removed the shadow of “ABA autism” searches. Remember, Google Trends doesn’t show raw search frequency, but here we can see that, compared to its own meager baseline, there might be developing a modest upward tick in searches for “ABA education.” If that’s so, it’ll be interesting to figure out what’s driving it.

Postscript 4: PBIS

In this post I’m mainly interested in instructional technologies, because they most directly address the perpetual failures of the American education system. PBIS has more of a behavior management focus, as does the Good Behavior Game, the other behavioral education technology I can think of that has achieved wide societal acceptance. But these aren’t irrelevant to the present discussion because behavior management problems create a drag on instructional effectiveness.

Postscript 5: It’s (Almost) Always About Decision Makers

If you want another example of why, in the quest to get effective technologies adopted, it’s critical to focus on decision makers, consider what practitioners in organizational behavior management (OBM) face every day. OBMers work with businesses and agencies to improve employee effectiveness and safety. In theory, they could try to approach each worker individually and try to work their magic, but this would be inefficient. And in any case behavior change usually requires contingency changes, and organizational contingencies are established by organizational decision makers. To get beneficial technologies in place at an organization-wide scale, work in OBM, therefore, is almost exclusively focused on systems changes.

Now, it’s not always the case that marrying effective interventions to public policy is the essential first step. Sometimes it’s possible to reach out directly to the public, as Azrin and Foxx did with their book Toilet Training in Less than a Day, which has sold some 7 million copies (and, through pediatricians and other professionals, influenced lots of parents who didn’t buy the book). About this example I’ll say only two things. First, an awful lot of behavior analysis books, including many that were intended for a general audience, never caught on quite like Toilet Training in Less than a Day (you can’t just wake up one morning decide to have a New York Times Bestseller). Second, this is a case where there’s no public policy infrastructure to harness; in other words, nobody regulates what method of toilet training you use, so reaching the public directly is the logical choice. By contrast, however, if your goal to make schools more effective, then your prospects for moving the needle of change are greatest if you work through the existing educational infrastructure.

Postscript 6: Components of Effective Reading Instruction

Reproduced from 2006 report, What education schools aren’t teaching about reading and what elementary teachers aren’t learning (download here), produced by the National Council on Teacher Quality.

THEME MUSIC