I’m doing okay. Well… actually, I’m tired. No, if I’m being honest, I’m exhausted. Lately, I’ve been feeling less productive than I’d like. And here’s the thing: my journey in understanding burnout feels a lot shorter than my journey living through it.

I’ve been a faculty member in public universities in the U.S. for nearly 20 years. Like many of you in higher education, summer often brings a change of pace; sometimes, a chance to catch our breath, maybe? Sometimes that slower pace gives us space to step back, take stock of the academic year, and reflect on where we are and how we’re really doing.

I know my perspective is shaped by my own experiences, but my hope is that this post speaks to anyone teaching behavior analysis or related fields. I acknowledge that summer may not mean more space for everyone, but whether summer or not, I am learning and here I share how space for pausing, reflection, self-compassion can be claimed through connection to alleviate and move toward wellness (Pope-Ruark, 2022).

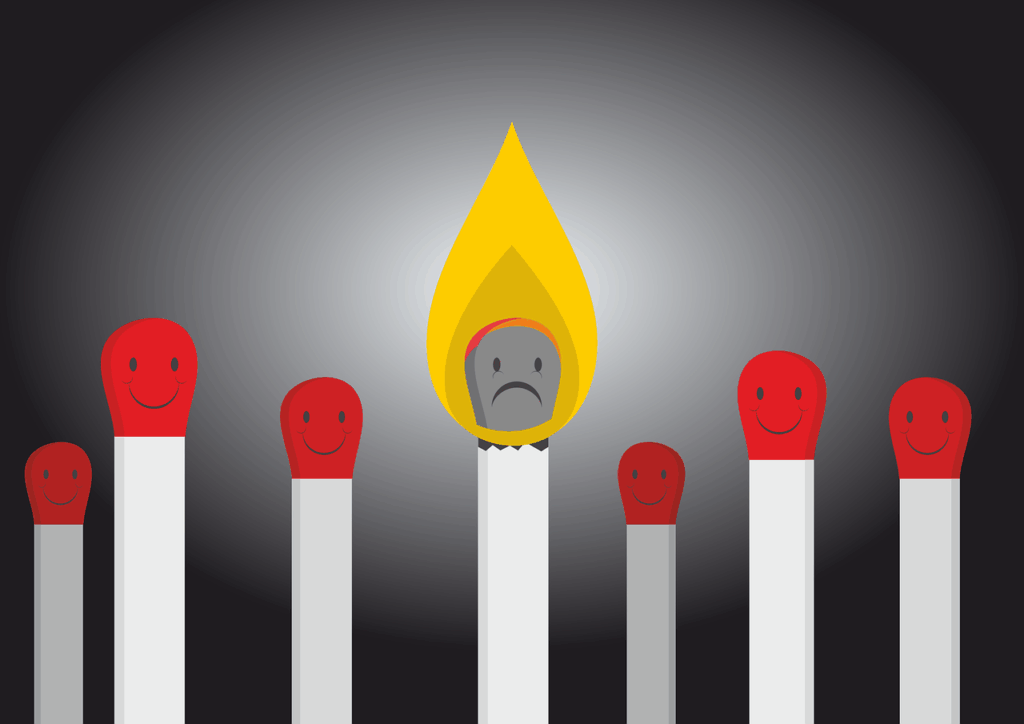

The focus here is burnout, a topic that’s only started showing up in the pages of some behavior-analytic journals in recent years, but one that many of us have felt for much longer. In particular, I’m interested in how our faculty are experiencing burnout and how I can help myself and others.

But first, what are we talking about when talk about burnout?

Searching for the Meaning of Burnout

As a researcher, I conducted a quick advanced search on PubMed. A search within the journal Behavior Analysis in Practice (BAP) yielded 51 results, with burnout as word within the text. According to this search, BAP has been publishing work within the topic of burnout since 2015 with peaks in publications starting in 2020 as we experienced the peaks of the COVID 19 pandemic.

One of the few articles in BAP that contains the term burnout within the title is by Julie M. Slowiak and Amanda C. DeLongchamp (2022). Reading Slowiak and DeLongchamp, I learned that Evangelina Demerouti et al. (2010) and Chritina Maslach and Michael P. Leiter (2016) define burnout as a psychological syndrome that emerges from prologued and stressful workplace demands and shows up as:

- Disengagement and cynicism – detachment from work, reduced or no identification with the organization, increased turnover intent

- Exhaustion – extreme fatigue, perhaps as in taking too much time to accomplish tasks that normally wouldn’t take so much time, compassion fatigue

- Feeling ineffectiveness or lack of accomplishment – one way to notice is reduced output (speaking up or writing)

The behavioral indicators for each of these three dimesions can be expanded and tailored.

Most of the literature on burnout published in BAP is about workers in applied behavior analysis (ABA), particularly in the area of developmental disabilities. This makes sense as this subfield of ABA has been growing quite rapidly. Still, the literature does not include the burnout of faculty. Although many of the articles could be generalizable to faculty, the burden is on the reader (presumably the faculty seeking this information) to extend this research from one professional field to another. Some things may be generalizable, but not others.

We can minimize the burden of having to generalize the ABA literature to the case of education, by reading research from other fields that have a longer history than behavior analysis in examining burnout at a general level. For instance, psychiatry. I recently learned from Rebecca Pope-Ruark (2002) that although not included as a clinical diagnosis in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM), that actually, burnout is considered an occupational phenomenon (not a medical condition) by the World Health Organization (WHO) and the International Classification of Diseases (ICD) (see WHO, 2025).

I also learned from Pope-Ruark (2022) that:

(…) while before the pandemic of 2020 there were only ocassional articles about burnout, it became one of the most talked about issues in the Chronicle and Inside Higher Ed during the pandemic (p. 46).

Ok, so can How can we Measure Burnout?

There are various inventories to assess and measure burnout, one by Christina Maslach and Michael P. Leiter called the Maslach Burnout Inventory (MBI). This inventory has been tested and revised since its first publication in 1981 and there is even a version for educators, the MBI Educators Survey (Maslach & Leiter, 2021). More uses of misuses of the MBI is available in, How to Measure Burnout Accurately and Ethically.

The Maslach Burnout Inventory (MBI) is the first scientifically developed measure of burnout and is used widely in research studies around the world. Since its first publication in 1981, the MBI has been applied for other purposes, such as individual diagnosis or organizational metrics. When used correctly, these applications of the MBI can greatly benefit employees and organizations (Malasch & Leiter, 2021)

The research on faculty burnout outside of the field behavior analysis points to something that we can agree upon, and that is that…

The Cause of Burnout is in the Environment

If you are experiencing burnout, you are not alone and it is not your fault.

One recurrent theme in the literature mentioned thus far is that burnout may be recognized at the individual level, but it is a function of the environment. Specifically, the academic environment of universities is increasingly demanding one and has been characterized as competitive, hierarchical, achievement-oriented, intellectual, evaluative, etc. There is also an expectation in many uiversities, that faculty should be doing more with less resources and support.

Zaynab Sabagh et al. (2018) identified how research on faculty burnout is scattered and conducted a review on existing empirical studies on the subject including faculty of various countries (e.g., China, India, South Africa, Spain, Turkey, United States). Sabagh et al. highlight how faculty burnout trickles down to student learning and institutional effectiveness. In understanding and proposing ways to address faculty burnout, these authors also consider the changes of higher education such as corporatization, massification, internationalization, yileding increasing demands for high quality teaching and high quantity research while competing for scarcing resources.

Academia breeds the belief that we must always be working and producing to be worthy and recognized. That’s exhausting. But then we don’t know how to relax and rest, so it’s a vicious cycle (Pope-Ruark, 2022, p. 164).

Although there are resources to address burnout at the individual level, ultimately institutional changes should be implemented to better address the problem. Not surpisingly the American Psychological Association (2023) stated why Employers need to focus on workplace burnout.

Burnout’s Double Bind: Women Carry the Burden and Lift Others Through It

The research on faculty burnout reveals that women and particularly those in minioritized groups are most vulnerable to burnout (see Pope-Ruark, 2022 for research). Academia as a hierarchical environment carries a heavy weight from a history of being a predominantly (in some cases solely) white and male setting. Pope-Ruark provides confessions and stories of women who reveal their detrimental experiences working in academia. In her book Pope-Ruark highlights the experiences of adjunct faculty.

While women in academia carry this weight, women also tend to lift others experiencing burnout (Pope-Ruark, 2022). The presence of women in the literature on faculty burnout is quite visible. As I prepared this post and conducted research on the topic of burnout, I noticed the names of the lead authors of the research that I chose to cite here and searched for them. I found that 100% of the references (journals and book included in the References section below) in this post are led by women. Notice that I used their first names in the text to highlight this fact.

Reflection, Compassion, and Connection as Paths Towards Wellness

During a recent workshop titled “The Space Between the Notes” led by Constanza Bartholomae (Associate Director of Teaching Support, Center for Teaching Excellence at Bryant University) and Ron Wasburn (Faculty Fellow at Center for Teaching Excellence at Bryant University) we explored how burnout often sneaks up on us because we’re so focused on our students and responsibilities that we forget to check in on ourselves. We also shared how we create pauses for reflection, confusion, and processing within our classes and our work days. How these pauses should be worked in rather than left “when we have time”. The space invited us all to slow down, and reflect together; this, as some of the research mentioned below may contribute to preventing or alleviating burnout.

My post includes many references to Rebecca Pope-Ruark’s book Unraveling Faculty Burnout Pathways to Reckoning and Renewal. This book offers many faculty stories and confessions that bring empathy, as well as resources for reflection and taking action toward wellness. Reflection, connection (inside and outside academia), and compassion (and self-compassion) come up as practices that can prevent and alleviate burnout.

Thank you to all the women that lift others up.

References

Demerouti E., Mostert K., & Bakker A. B. (2010). Burnout and work engagement: a thorough investigation of the independency of both constructs. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 15(3), 209-222. doi: 10.1037/a0019408

Maslach, C. and Leiter, M.P. (2016), Understanding the burnout experience: recent research and its implications for psychiatry. World Psychiatry, 15, 103-111. https://doi.org/10.1002/wps.20311

Pope-Ruark, R. (2022). Unraveling faculty burnout. Pathways to reckoning and renewal. Johns Hopkins University Press.

Sabagh, Z., Hall, N. C., & Saroyan, A. (2018). Antecedents, correlates and consequences of faculty burnout. Educational Research, 60(2), 131–156. https://doi.org/10.1080/00131881.2018.1461573

Slowiak J. M, DeLongchamp A. C. (2021). Self-care strategies and job-crafting practices among behavior analysts: Do they predict perceptions of work-life balance, work engagement, and burnout? Behavior Analysis in Practice, 15(2): 414-432. doi: 10.1007/s40617-021-00570-y

I wanted to write a comment but just couldn’t muster the energy.

You still did 🙂