This blog was guest written by Emily Sullivan, Ph.D., BCBA-D, LBA, and Amanda Morris, M.S., BCBA, LBA

If you just passed the exam, congratulations! That’s no small accomplishment. It’s a reflection of the hard-earned educational and clinical experiences you completed during your graduate program. But passing the exam is only the start of your career as a Board Certified Behavior Analyst (BCBA).

Here’s the truth: no graduate program fully prepares a new BCBA for everything they’ll face on the job. It’s stressful and that can contribute to burnout, which is increasing at an alarming rate. Many clinicians cite the same reasons for burnout: lack of preparation for their role and limited support once they are in the role. We’ve both had moments where we wondered if we should walk away—open a bakery, or join the circus. (Both seem oddly appealing). But we stuck with it, and we credit mentorship, the support of colleagues, and our ability to find reinforcement in clinical successes as drivers that helped us continue to find joy in the work.

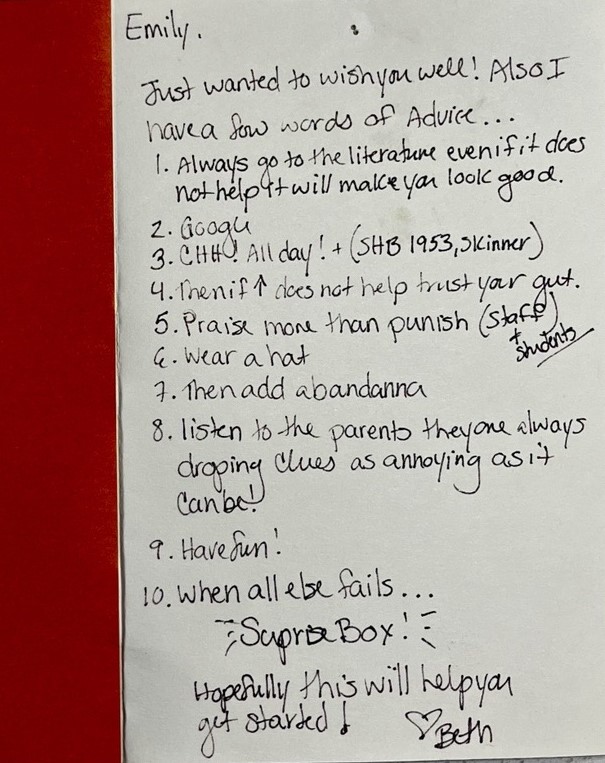

Not long after I (Emily) passed my BCBA exam, I stepped into a new role at a different organization. Just before I made the leap, my previous supervisor gifted me a card with a surprise box (an inside joke). The surprise box was filled with goodies, which I appreciated, but the card was the actual gift. It was a list of her advice for my next role. I’ve carried this list to every job I’ve had since then.

Each time I read it, I learn something new, and I try to pass on similar advice to my supervisees or colleagues. Here are the six most important lessons I have learned

.

.

Lesson 1. You don’t know everything; you will be wrong more often than you are right.

No number of degrees, certifications, or licensures will make you an all-knowing expert—and that’s okay. As a BCBA, you might feel pressure to have all the answers, especially when working with supervisees, colleagues, or supervisors. But the truth is, you’ll find yourself making mistakes. You’ll get things wrong. It does not reflect your abilities or worth as a professional; it means you’re learning.

Sometimes, another clinician might question why you recommended a particular intervention to a caregiver or omitted specific details in a treatment plan. This can trigger a defensive reaction, but look at them as just questions—opportunities to clarify your thinking and reflect on your choices. Supervisors ask questions to gather information and help you improve, not to tear you down. Instead of reacting defensively, explain your rationale and open an honest dialogue.

Feedback is also more direct when you’re a supervisor. And yes, it can sting. But corrective feedback is part of your growth. Consider what’s being said. Pause for a moment, digest the feedback, and ask how you can best approach the same situation in the future. If you feel emotional or the timing is bad, thank your supervisor and suggest revisiting the conversation later, once you’ve had time to process the feedback.

By receiving feedback graciously, you may develop a better relationship with your supervisor, one in which you can communicate early and often with each other, even when it is uncomfortable. Nothing is more uncomfortable than allowing problems to go unaddressed and adversely impact interpersonal dynamics. Skills like active listening and perspective taking can go a long way. Resources like Crucial Conversations or articles on soft skills can help. Feedback, no matter where it comes from, is a resource, not just a critique. How you respond to it will shape professional relationships and help you become a model for your supervisees.

Lesson 2. Don’t be afraid to ask for help. No one expects you to have all the answers.

Everyone asks for help, even when it doesn’t seem that way. The fastest path to the right answer is often by asking a simple question. Your colleagues are one of your best resources, so don’t hesitate to lean on them and ask questions. If your immediate circle doesn’t have the answers, consider reaching out to experts. Many professionals you think are too busy or too prestigious are happy to respond.

Take, for instance, a situation where your colleague asks for guidance on issues outside your scope of competence. Say their client is diagnosed with a pediatric feeding disorder, and your colleague asks for advice on how best to approach the family’s concerns. If you haven’t received formal training in feeding, the ethical thing to do is to stay within your scope of competence. Tell them you don’t know, and maybe even help them contact a feeding expert for consultation. No single BCBA is an expert in everything, and recognizing that is key to your professional growth.

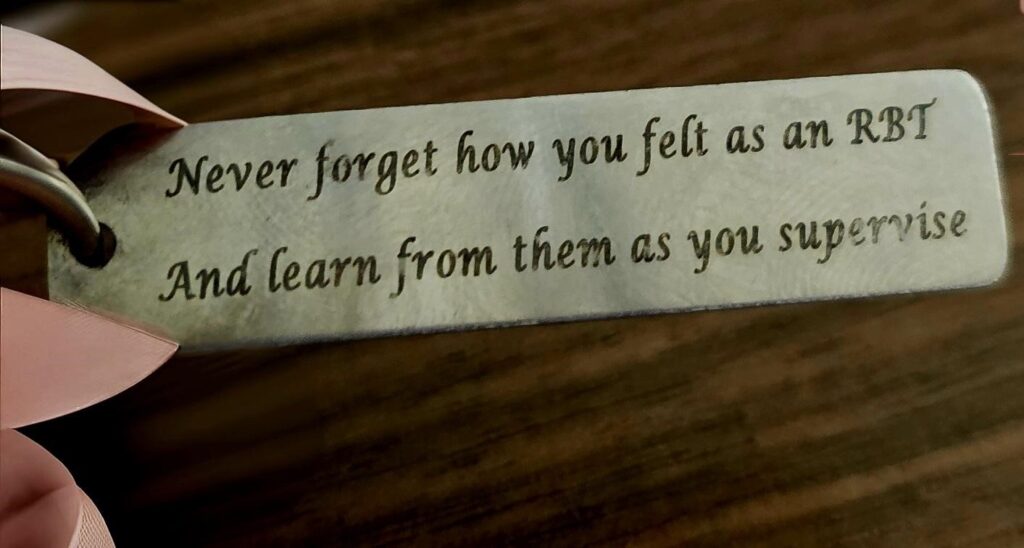

This applies to supervision, too. When you first become a BCBA, it can feel surreal to suddenly be supervising RBTs or trainees—especially when you were in their shoes not long ago. You may wonder: How am I supposed to know how to supervise already?

The best place to begin is by building a strong supervisory relationship. Start with rapport. Talk about how each of you prefers to receive feedback and how you learn best. That kind of honest dialogue creates a foundation for real growth. Feedback, as we’ve already talked about, is essential—for your supervisees and for you. It’s critical to create a space where learning is safe, feedback is mutual, and trust runs in both directions. If you want honest feedback from your supervisees, you’ll need to model what that looks like. Let them know their input matters and that you’re open to changing your approach to support their learning. Because you can’t change what you don’t know needs changing.

Some great resources for building strong supervisory relationships include:

- Recommended practices for individual supervision: Considerations for the behavior-analytic trainee (Helvey et al., 2022)

- Recommendations for detecting and addressing barriers to successful supervision (Sellers et al., 2016)

- Recommended practices for individual supervision of aspiring behavior analysts (Sellers et al., 2016)

Being a good supervisor involves more than building a strong relationship with your supervisee. There’s also the behind-the-scenes work: documentation requirements, tracking hours, and teaching your supervisees to become independent managers of their own progress. It’s a lot to juggle. While the BACB provides a wealth of resources on supervision, assessment, training, and oversight, navigating it all at the start can feel overwhelming. When we began supervising RBTs and aspiring BCBAs, we found certain articles and tools useful. Many of them align with the BACB’s supervisor training curriculum outline, and we recommend them as a solid starting point:

- Designing a successful supervision journey: Recommendations and resources for new BCBA supervisors (Fraidlin et al., 2023)

- The benefits of group supervision and a recommended structure for implementation (Valentino et al., 2016)

While we’ve found many articles and tools helpful, we both adapted and created supervision systems that made sense for our own work. The goal isn’t to copy someone else’s system perfectly—it’s to build something you’ll actually use and that makes sense for your clinical setting. Finding a great mentor can be a huge help in this process, and it meets the January 1, 2022, BACB requirement for a Consulting Supervisor.

During supervision with aspiring BCBAs, we love covering these articles as the foundation of clinical practice.

The Basics:

- Some current dimensions of applied behavior analysis (Baer et al., 1968)

- Some still-current dimensions of applied behavior analysis (Baer et al., 1987)

- Toward effective and preferred programming: a case for the objective measurement of social validity with recipients of behavior-change programs (Hanley, 2010)

- A proposed model for selecting measurement procedures for the assessment and treatment of problem behavior (LeBlanc et al., 2016)

- The scientist/practitioner in behavior analysis: A case study (Sidman, 2024)

- An implicit technology of generalization (Stokes & Baer, 1977)

- Social validity: The case for subjective measurement or how applied behavior analysis is finding its heart (Wolf, 1978)

Deeper Dive:

- A call for discussion about scope of competence in behavior analysis (Brodhead et al., 2018)

- The fuzzy concept of applied behavior analysis research (Critchfield & Reed, 2017)

- There is no such thing as a bad boy: The circumstances view of problem behavior (Friman, 2021)

- Humble behaviorism redux (Kirby et al., 2022)

- The analysis of behavior: what’s in it for us? (Sidman, 2007)

Lesson 3. You’re a supervisor now. Don’t ask anyone to do anything you wouldn’t do yourself.

As a BCBA, your responsibilities extend beyond direct client care. You’re a supervisor now, which means your role is different from an RBT’s—and it requires a shift in how you think about your work. Supporting your client remains top priority but so does supporting the caregivers and staff around that client.

When you recommend strategies or write treatment plans, ask yourself: Would I be willing to do this? Could someone else do this with consistency and confidence? If the answer is no, rethink the plan. Take, for example, a client with attention-maintained behavior who can persist for hours in an extinction condition. You might be able to implement a long extinction protocol—but asking a caregiver or staff member to withhold attention for hours while still monitoring the behavior closely? That’s likely not sustainable or fair. Instead, practice perspective-taking. Ask what’s realistic and humane, not just what’s technically possible.

When designing treatment plans, remember the philosophical assumption of parsimony. We have an impressive array of behavior analytic procedures at our disposal. Different approaches can often lead to the same outcome. Often, less is more. As Robert Epstein said in 1984:

“Where we have no reason to do otherwise and where two theories account for the same facts, we should prefer the one which is briefer, which makes assumptions with which we can easily dispense, which refers to observables, and which has the greatest possible generality.” (Epstein, 1984, p.119)

You’ll encounter challenging cases. In those moments, you may feel pressure to act—to tweak the behavior plan, to add a new intervention, to show that you’re doing something. It’s a natural impulse. But sometimes, the urge to respond quickly can lead to overcomplicated, over-resourced treatment plans. You might find yourself layering on a token system, differential reinforcement procedures, or visual supports—all at once—in hopes of addressing a new concern. But more isn’t always better.

Before adding something new, ask yourself: Do I really need to add that? What are the data telling me? Is there something I still need to learn before making a change? Acting with intention, rather than urgency, helps you design more effective, sustainable interventions.

Lesson 4. It’s okay to feel overwhelmed; focus on what you can control.

There will be days when the number of tasks on your plate feels impossible. When that happens, take a breath. Step back. And focus on what you can control. Start by identifying the most pressing issue and tackling that first. Gain traction in one area to bring clarity to the others.

Picture this: it’s 2 p.m., and your supervisor needs progress notes by 5. Just as you start pulling materials together, your phone rings. Before you can answer, a supervisee rushes in with a client crisis. It’s overwhelming, and you feel like you have to do everything at once. You’re one person. The paperwork can wait. The call can be returned. Safety comes first.

Even when you can’t control the chaos around you, you can focus on noticing your private experiences and using tactics to reach calm. One strategy is to take inventory of your covert behavior and track patterns over time. You might also rework your schedule or make a clear priority list. You might have a candid conversation with your supervisor about adjusting your workload, redistributing responsibilities, or seeking support outside of work from a counselor, coach, or therapist. These are activities you can control that bring calm to the chaos of clinical practice.

And when clients have tough days, which they will, it can feel like the weight of their progress is entirely on your shoulders. But your job isn’t to ensure perfection every day. Your job is to teach. To help your clients build skills. That work is challenging. When they have a tough day, it doesn’t mean you’ve failed—and you’re not alone in feeling the pressure. Your RBTs, caregivers, and even your clients feel it too.

That’s why self-care is essential. We have learned to prioritize self-care, especially when the warning signs of us neglecting our health start to show. Sometimes it’s planning time with friends or family. Sometimes it’s taking a day or two off before things reach a boiling point. And for a longer-term approach, we recommend the Finch app, which gamifies self-care and helps hold you accountable in a fun, manageable way. Whatever your strategy, build it in before you burn out. You—and everyone around you—will be better for it.

Lesson 5. Remember to go back to basics. Often, the answers are hidden in the literature.

The basic principles you learned in school were taught for a reason, they’ll remain central to your practice throughout your career. Let’s say you’ve just been assigned a new RBT to supervise, but you realize your familiarity with certain technical terms has drifted. That’s normal. But it’s your responsibility to go back to the foundations: read, engage with research, attend conferences, and talk with colleagues.

As you advance in your career, you’ll encounter increasingly complex cases. It’s easy to feel overwhelmed when nothing seems straightforward—when setting events are fleeting, or when your client suddenly stops demonstrating skills you thought were mastered. Return to foundational principles to help you stay conceptually systematic as you explore solutions, some of which may not exist in the clinical literature. Ask: Under what conditions does this behavior turn on or off? Begin there. Focus on rapport. Take time to connect with the client, caregivers, and staff before diving into new interventions. Ground yourself in the basics and build upward.

Engaging regularly with the literature—especially when you’re stuck—does more than keep your skills sharp. It reconnects you with science and helps you approach challenges with a sense of clarity and purpose.

Lesson 6. Always value compromise; don’t compromise your values.

Working with clients, caregivers, and staff calls for flexibility. Rarely are situations black and white. Compromise can be one of your strongest tools for building trust and rapport, especially when navigating different perspectives and priorities. But while compromise is essential, your core values are not negotiable.

If you find yourself repeatedly facing situations that challenge your ethics—like being asked to supervise more RBTs than you can support, take on a case outside your scope of competence, or mislead a caregiver to appease a supervisor—those aren’t gray areas. Those are red flags.

In those moments, know this: you are the commodity. Your skills, judgment, and ethical commitment matter—and they are in demand. If something feels off, you have options. Don’t hesitate to reach out to resources like the ABA Ethics Hotline, consult trusted mentors, or explore reputable job forums. Your professional integrity is worth protecting.

Go Forward

We hope this article shared some lessons we have learned throughout our careers. Bookmark this article, or the resources in it, and revisit it throughout your first year. Sometimes these lessons aren’t apparent until you are faced with a challenge you need to solve. Focus on careful self-management and attention to your behavior, so you can show up for your clients, colleagues, and supervisees, and contribute to a field that impacts thousands of lives. Good luck out there!

The writing and editing of this blog were supported by Wider Reach Incubator, an initiative that helps students, researchers, and practitioners in behavior analysis write for and publish in mainstream outlets. Wider Reach offers workshops and coaching for university programs, research labs, state and international affiliates, and service organizations. For more information, contact widerreachincubator@gmail.com.